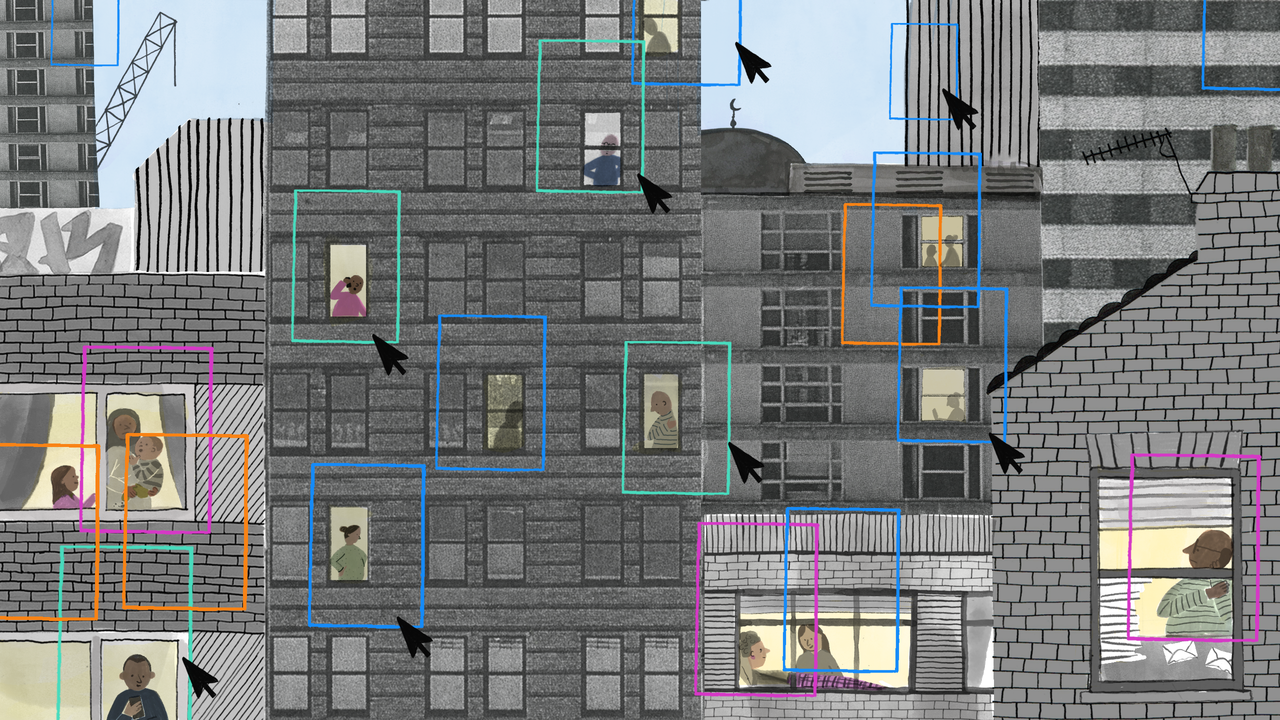

The adoption of predictive analytics in public administration is typically justified by two pillars: austerity and accuracy. Governments and private organizations argue that automated decision-making systems reduce administrative bloat while eliminating the subjectivity of human caseworkers. For example, the Dutch government explicitly framed its automated child care benefit fraud system as a means to replace human discretion with objective, data-driven risk scoring. However, the operational realities of these systems suggest different outcomes. Rather than eliminating bias, they frequently manipulate it to embed historical inequalities into the architecture of seemingly neutral code. The threat to marginalized communities is not that technology fails, but that it works as designed and amplifies the systemic discrimination that policies are meant to alleviate.

This dynamic is most evident in the digitalization of the welfare state. When government agencies turn to machine learning to detect fraud, they rarely start with a blank slate and train their models on historical enforcement data. These datasets are saturated with selection bias because low-income and minority populations have historically faced higher rates of surveillance and policing. Lacking sociopolitical context, the algorithm interprets this overrepresentation as an objective indicator of risk, identifying correlations and developing them as causation.

The fallout from this logic was evident in the Dutch childcare benefit scandal mentioned above. foot troubletens of thousands of families were wrongly accused of benefit fraud. The system’s design treated dual nationals and low-income individuals as agents of deception and penalized them. This is a classic example of a statistical model carrying out the narrow imperative of maximizing the state’s fiscal recovery without the countervailing imperative of preserving due process for the public. If the accusations were made correctly, the state benefited, but if the system went wrong, all the damage would fall on the wrongly accused citizens.

Similar asymmetries plague the private sector, particularly the labor market. The proliferation of algorithmic hiring tools promised to democratize hiring by blinding selectors to demographic indicators, but ongoing lawsuits Mobley vs. Workday The US has highlighted the limitations of “blind” algorithms. If the model is optimized to select candidates similar to current top performers, and the current workforce is homogeneous, the algorithm will penalize applicants from non-traditional backgrounds. You don’t need to know a candidate’s race or disability status to discriminate against them. All you need to do is identify data points (postal codes, employment disparities, specific language patterns) that correlate with these protected characteristics.

This poses a major challenge to existing liability frameworks. In Europe, discrimination law distinguishes between direct and indirect discrimination, with the latter occurring when seemingly neutral rules or practices unfairly disadvantage a protected group, without requiring proof of intent. But algorithmic discrimination is pervasive and difficult to challenge. Rejected job applicants or reported welfare recipients rarely have access to their own disqualifying scores, let alone training data or weighting variables. They are faced with a black box that results in unfounded decisions. This opacity makes it nearly impossible for individuals to challenge results and effectively insulates implementing organizations from responsibility. The burden of proof is on the party with the least information.

To their credit, regulators are trying to catch up. Although the EU’s AI law and new US state laws introduce requirements for impact assessment and transparency, enforcement remains a theoretical challenge. Most current auditing methods focus on technical fairness metrics, essentially adjusting calculations until error rates appear balanced across groups. This technical red tape misses the broader point that a system can be statistically “fair” but still be predatory, often when the underlying policy objective is punitive. If the very premise of mass surveillance of the poor is wrong, then adjusting the algorithm that flags poor households for fraud investigation at the same rate regardless of race will not solve the problem.

Policy interventions must go beyond error rate optimization and formal parity measurements. Treating fairness as a matter of adjusting statistical output assumes that the main problem lies in measurement errors rather than the social and institutional conditions that generate the data in the first place. Algorithmic systems do not observe the world directly. They inherit their views of reality from datasets shaped by previous policy choices and enforcement practices. Responsible evaluation of such systems requires scrutinizing the origins of the data on which decisions are based and the assumptions encoded in the variables chosen.

This is particularly evident in the use of proxies, which are measurable stand-ins for complex social attributes that are difficult or politically sensitive to directly influence the state. Variables such as length of phone calls, frequency of address changes, social network density, and patterns of online interactions are often presented as neutral indicators of an individual’s trustworthiness or trustworthiness, but in reality they serve as indirect measures of class, instability, migration status, disability, or caregiving responsibilities. Because these attributes are unevenly distributed across society, proxy-based systems systematically penalize those whose lives do not conform to the behavioral norms of the datasets they are evaluating.

The essential problem is that these proxies reduce complex social reality to fragments of behavioral data, stripped of context and interpretation. Short calls may indicate trust limitations, language differences, or time pressure rather than avoidance, while sparse digital networks may reflect age, poverty, or deliberate withdrawal from online platforms rather than social isolation or risk. Once such signals are elevated to definitive indicators, the system engages in a type of digital phrenology, inferring personality and future behavior from surface traces that have only an incidental relationship to the quality being judged.

These discursive shortcuts disproportionately harm individuals with non-standard or unstable digital footprints, individuals whose lives are shaped by irregular work, informal care, migration, or limited access to infrastructure. These are often the same groups that are already subject to intense surveillance by welfare agencies and public authorities. Algorithmic systems compound the disadvantage by treating deviations from statistical norms as evidence of risk while presenting this judgment as the result of objective analysis rather than a choice built into the system design.

The danger of these systems is that political decisions can be laundered through technical processes. By viewing allocation and enforcement as engineering problems, agencies can avoid the moral and legal scrutiny that typically accompanies policy change. For the communities at the forefront of these decisions, the result is a reinforcement of social hierarchies enforced by bureaucracies that are more invisible, harder to understand, and much harder to fight.