Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of glioblastoma patients in SEER and test sets are shown in Table 1.p<0.05) This could mean heterogeneity in the data, but other demographic and clinical features remained comparable across cohorts.

Identifying risk factors for glioblastoma patients

Identifying risk factors for the OS

Univariate and multivariate COX regression analyses were performed to screen for important predictors of OS in the SEER set (n= 1207) and test set (n= 172). As shown in Table 2, age, histological type, combined summary stages, surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy were identified as independent prognostic factors for OS in the SEER set (p<0.05). In the test set, age, tumor history, histological type, surgery, and chemotherapy were screened as statistically significant prognostic factors for glioblastoma patients (p<0.05). To address potential selection biases in tumor history of OS, we used IPTW strategies to generate weighted cohorts using diagnosis year, age, gender, histological site, major site, left and right, tumor size, summary summary stage, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. As shown in Table 3, tumor history continued to be an independent predictor of worse OS after adopting IPTW (HR: 2.06, 95% CI: 1.30–3.25, p= 0.002) strengthens association robustness, but no significant differences were investigated after IPTW in the Seer set.

Identifying CSS risk factors

Detailed univariate and multivariate COX regression analysis results for SEER and test set CSS are shown in Table 4.p<0.05). The test set confirmed that age, tumor history, histological type, surgery, and chemotherapy are independent and important factors in CSS (p<0.05). We used IPTW techniques to create weighted cohorts based on diagnosis, age, gender, histological site, major site, left and right, tumor size, tumor size, surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy years to address potential selection biases in tumor history in CSS. As shown in Table 5, tumor history remained an independent predictor of worse OS after IPTW (HR: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.30–2.86, p= 0.001) Test set to check the strength of the relevance.

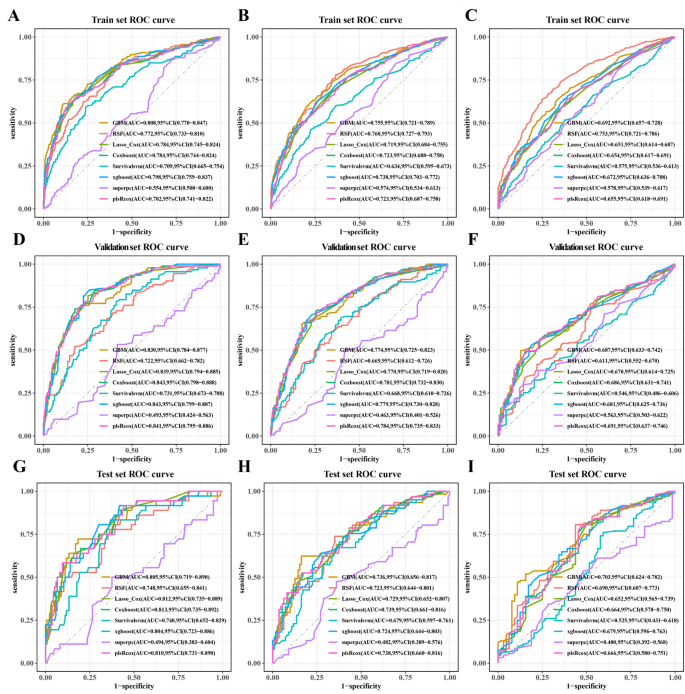

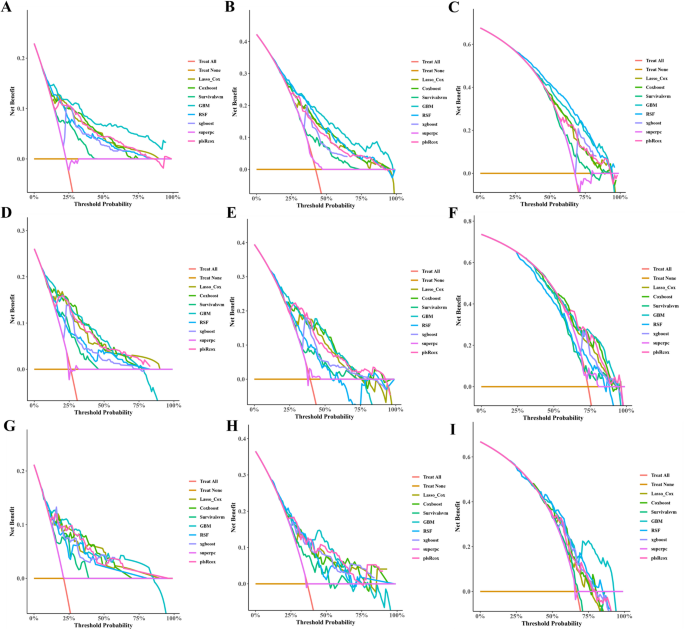

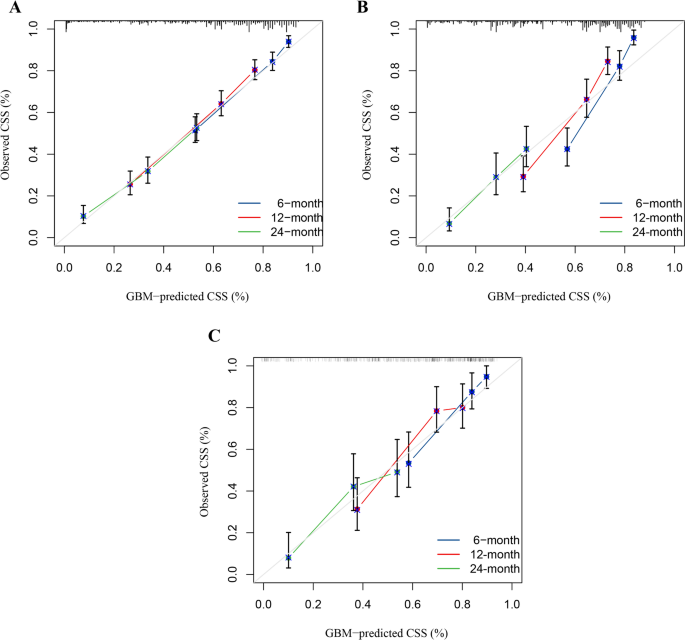

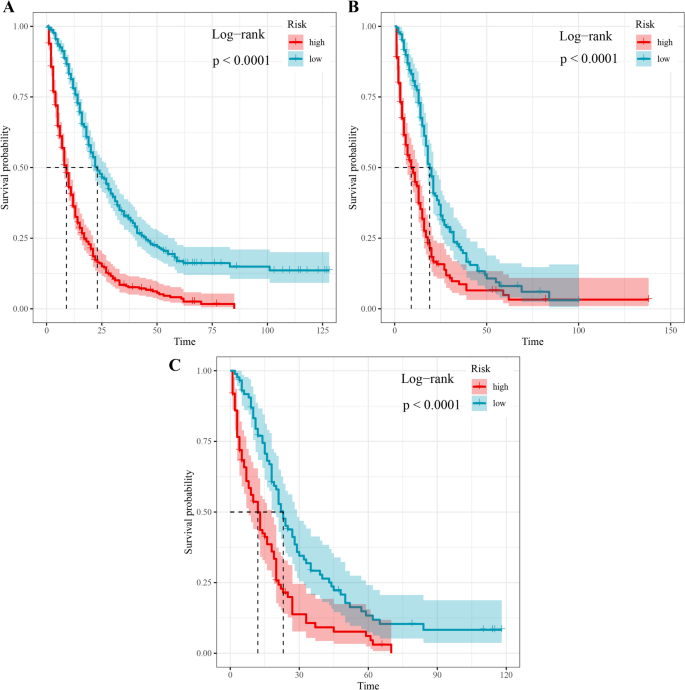

Machine learning-based prediction models for OS

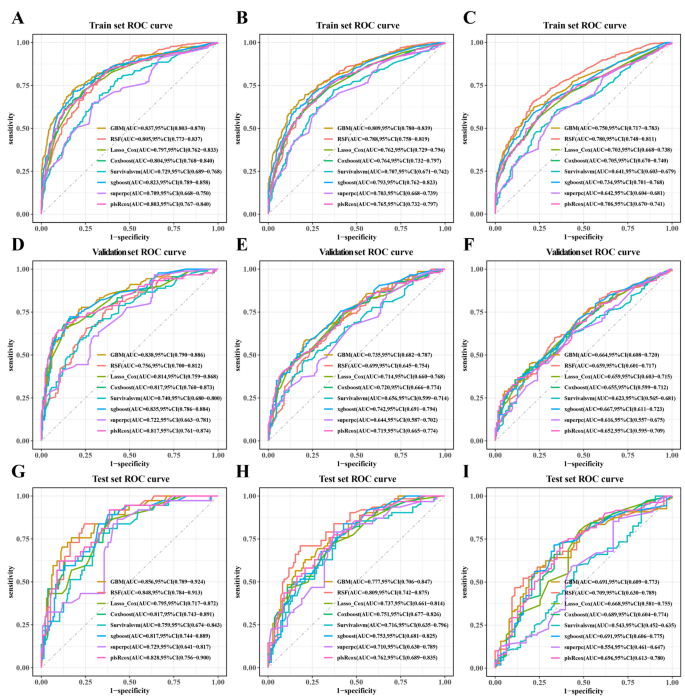

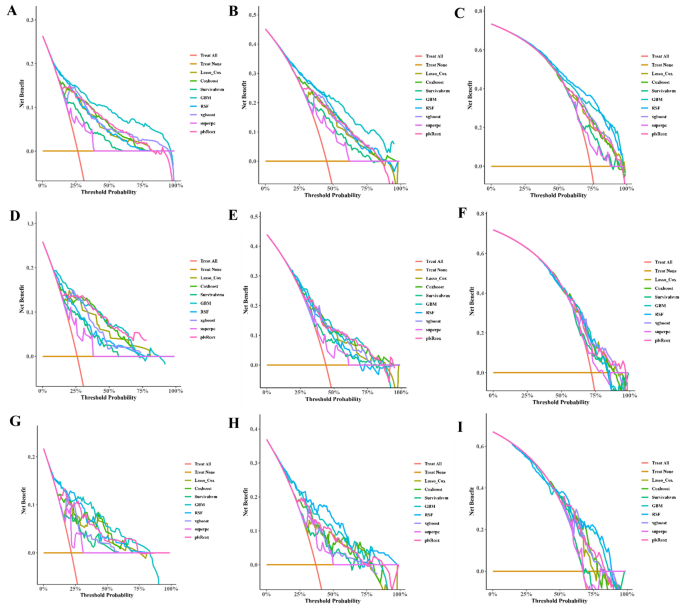

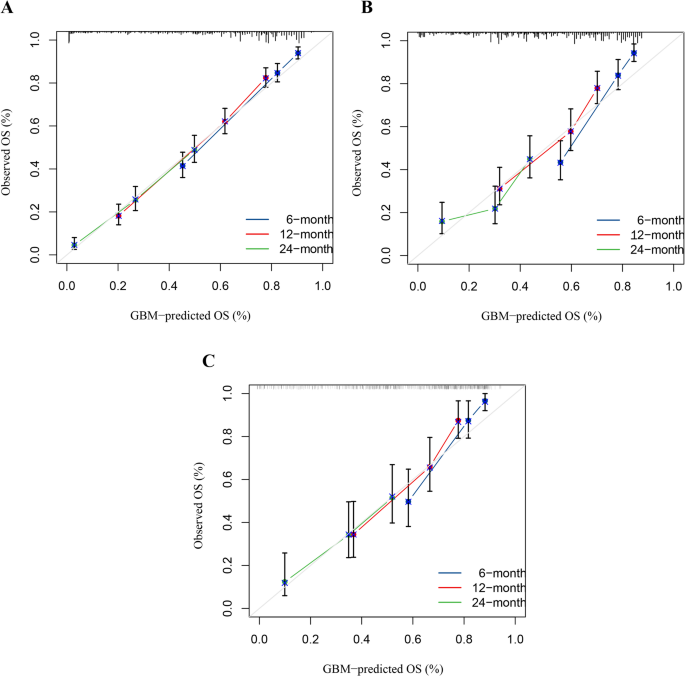

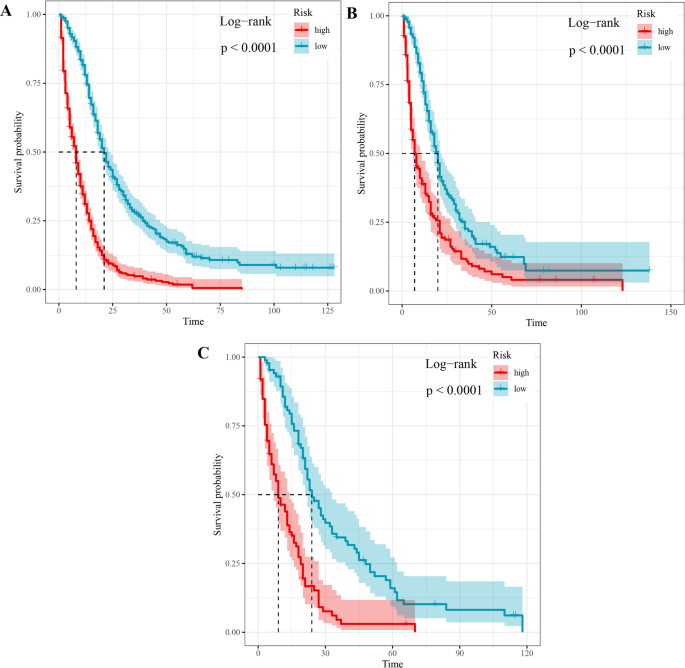

Univariate COX regression was used to select features in the training set. As shown in Table 6, nine features were statistically significant, including age, tumor history, histological type, left and right, tumor size, combined summary stage, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, and were selected for constructing a predictive model. Several machine learning algorithms, including RSF, GBM, Lasso Cox, CoxBoost, Survival-SVM, XGBoost, SuperPC, and PLSRCOX, were used to develop a prognostic framework that could estimate the probability of OS at 6, 12, and 24 months intervals. As the ROC curve in Figure 1. Show in Table 7, GBM model showed excellent predictive performance at 6 months (AUC = 0.837, 95% CI: 0.803–0.870), 12 months (AUC = 0.809, 95% CI: 0.780–0.839), and 24 months (AUC = 0.750, 95% CI: 0.717–0.783). Verified with validation and test sets. The DCA curve also suggested that the GBM model retains considerable utility in making clinical decisions (Fig. 2). The GBM model showed good agreement between the predicted and observed OS rates at 6, 12 and 24 months in training, validation, and test sets, as shown by the calibration curve (Fig. 3). The survival curves in Figure 4 show differentiation capabilities between low-risk and high-risk OS patients in training, validation, and test sets (p<.05).

Receiver operating characteristic curves for 6-month, 12-month and 24-month OS prediction models for glioblastoma patients in training (AC),verification(DF), and test (gi) Set.

Decision curve analysis (DCA) of 6-, 12- and 24-month OS prediction models for glioblastoma patients in trainingAC),verification(DF), and test (gi) Set.

Calibration curves for the 6-month, 12-month and 24-month OS predictions in training (a),verification(b), and test (c) Set.

Survival curves between low- and high-risk glioblastoma patients with OS.

Machine learning-based prediction models for CSS

As shown in Table 8, seven characteristics including age, primary site, lateral orientation, combined summary stages, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy were statistically significant as confirmed by univariate Cox regression and incorporated to establish predictive models. Of the eight machine learning algorithm-based models, RSF, GBM, Lasso Cox, CoxBoost, Survival-SVM, XGBoost, SuperPC, and PLSRCOX, the GBM model showed the best predictive performance in the training set at 6 months (AUC = 0.808, 95% CI: 0.770–0.847), 12 months, 0.847) for the training set, as shown in Table 9, 0.721–0.789) and 24 months (AUC = 0.692, 95% CI: 0.657–0.728). Figure 5, and the validation and test sets, also confirmed the effectiveness of the predictive effects. The utility of the GBM model for clinical decision-making was suggested by the DCA curve (Fig. 6). Calibration curves for the GBM model in training, validation, and test sets showed good agreement between predicted overall survival and observed overall survival at 6, 12 and 24 months (Fig. 7). As shown in Figure 8, Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed statistically significant stratification.p<0.05) Results of CSS outcomes between low- and high-risk subgroups in training, validation, and test setsp<0.05).

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month CSS prediction model for glioblastoma patients in training (AC),verification(DF), and test (gi) Set.

Decision curve analysis (DCA) of 6-, 12- and 24-month CSS prediction models for glioblastoma patients in trainingAC),verification(DF), and test (gi) Set.

Calibration curves for the 6-month, 12-month and 24-month CSS predictions in training (a),verification(b), and test (c) Set.

Survival curves between low- and high-risk glioblastoma patients with CSS.