The Bose-Einstein condensate system

We create a bosonic quantum system by trapping about 2 × 10587Rb atoms. This system forms a BEC at low temperature, about 50 nK in our experiment (Fig. 1). The atomic BEC is loaded in a triangular optical lattice to suppress unwanted real-space dynamics23. After preparation of the lattice BEC system, the optical lattice and the trapping potential are shut-off, which then let the atoms expand ballistically. Performing the time-of-flight (TOF) technique (see Supplementary Note 224) in the experiment, we measure the momentum distribution n(k). It takes about T0 = 38 s to complete one experimental cycle. Details of our experimental setup can be found at ref. 23.

a The schematic diagram of experiment setups for an atomic Bose-Einstein condensates (BEC) based force sensor. The atomic BEC is confined by a triangular optical lattice spread in the x-y plane. The time-of-flight image is probed by an imaging laser beam along the z direction, and showing on the CCD camera. With an external force applied on the BEC, the time-of-flight (TOF) image would develop systematic shifts. The signal can be automatically generated by inputting the TOF image into the well-trained machine-leaning model. b The workflow of an anomaly detection method for force sensing. It involves the utilization of a generative machine learning model comprising a generator and a discriminator for digitally replicating the experimental time-of-flight images. The anomaly detection is assisted by introducing an additional encoder. All three components are deep artificial neural networks. The anomaly score (AS) is composed by residual loss (RL) between input data x and its digital replica \(\tilde{x}\) and discrimination loss (DL) generated by the discriminator.

In the time-of-flight measurements, we have shot-to-shot noise. There are quantum shot-noises, which arise from quantum superposition of different momentum eigenstates due to atomic interactions, trapping potentials, and optical lattice confinement. There are thermal noises. Although the atomic BEC is cooled down to 50 nK, we still have thermally activated atoms. These atoms induce stochastic fluctuations in the measurement outcomes. There are also technological noises. The control of the atom numbers, the trapping potential, and the optical lattice depth are not perfect in the experiment. They may have noticeable or unnoticeable drifts in different experimental runs. As a result, the TOF measurement outcomes in the consecutive experimental runs would unavoidably fluctuate from shot to shot. We thus denote the measurement outcomes as nα(k), with α indexing different experimental runs.

In detecting an external force acting on the BEC, a standard approach is to examine the response in the averaged center-of-mass (COM) momentum, i.e.,

$${\overline{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{COM}}}}}}}}}=\frac{{\sum }_{\alpha }\int{d}^{2}{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}{n}_{\alpha }({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}){{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}{{\sum }_{\alpha }\int{d}^{2}{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}{n}_{\alpha }({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})}.$$

(1)

Although the measurement outcome nα(k) is a two-dimensional image, which potentially involves very rich information, the conventional approach of data processing following Eq. (1) only consumes the zeroth and first order moments of the two-dimensional data, leaving behind higher-order correlations.

The digital replica

In order to incorporate the full information in the measurement outcomes, nα(k), one plausible way is to perform digital twinning of the physical system by matching the probability distributions. It then automatically takes into account high-order correlation effects. Since the atomic BEC system in the experiment has noises of various origins, it is impractical to simulate the experimental measurement outcomes using conventional modeling approaches, for example by simulating Gross-Pitaevskii equations25,26. In this study, we create a digital twinning of the experimental system, by implementing a generative machine learning model, which incorporates quantum, thermal, and technical noise channels simultaneous at equal-footing in a purely data-driven approach.

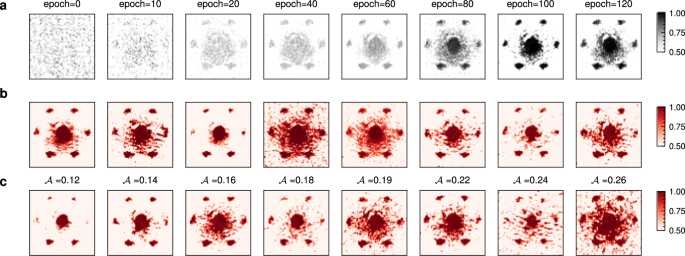

We implement a generative adversarial network (GAN)27 for digital twinning of the atomic BEC. GAN consists of a generator G( ⋅ ) that attempts to map a latent vector z to a realistic data of momentum distribution, G( ⋅ ): \({{{{{{{\bf{z}}}}}}}}\mapsto \tilde{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\), and a discriminator D( ⋅ ) that tries to differentiate the real data, n(k), from the fake data from the generator, \(\tilde{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})=G({{{{{{{\bf{z}}}}}}}})\). The two networks are trained simultaneously, with the generator attempting to produce data that can fool the discriminator, and the discriminator learning to correctly identify synthetic data (Methods). The generator and discriminator are realized by two parameterized deep neural networks, denoted as G(z; θG) and D(n(k); θD). We collect 3.6k independent measurements of momentum distributions for force-free experiments, and feed them to GAN (see Supplementary Note 324). This amount of data takes about forty hours to collect in experiments, which is reasonably affordable. In Fig. 2a, we present fake data produced by the generator during training procedure, where the generated data is visually similar to real data, indicating that the model is capable of capturing the underlying data distribution without model collapsing. The trained generator produces a digital replica (Fig. 2b) of the experimental measurements (Fig. 2c), which could generate fluctuating configurations involving all noise channels automatically.

a The momentum distribution constructed by generative machine learning model at different training epoch. We present several images generated from a fixed generator, namely the digital replica in b. c shows eight representative real time-of-flight images with anomaly scores from 0.12 to 0.26.

As in the experimental data that has typical and atypical configurations due to noises, the digital replica also generates typical and atypical configurations. Within the framework of GAN, the degree of atypicality is quantified by an anomaly score,

$${{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}))={{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{R}(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}))+\lambda \cdot {{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{D}(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})).$$

(2)

The anomaly score combines both residual loss and discrimination loss, serving to quantify the atypicality of an input image n(k) in comparison to its corresponding digital replica \(\tilde{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\). Specifically, the residual loss (RL) \(\left.{{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{R}=\parallel n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})-\tilde{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\right){\parallel }_{2}\) is produced by adding an encoder in front of the generator (Fig. 1), assessing the Euclidean distance between the real image and its corresponding digital replica. The discrimination loss (DL) \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{D}(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}))=\parallel h(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}))-h(\tilde{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})){\parallel }_{2}\) is directly given by the feature layer h( ⋅ ) of the discriminator (see Supplementary Note 424). The encoder is trained by minimizing the residual loss. The weighting coefficient \(\lambda \in {\mathbb{R}}\) is a hyper-parameter that balances RL and DL. These two components evaluate the discrepancy between fake and real data in terms of image distance and feature discrimination. We choose λ = − 0.76 for an optimal sensitivity (see Supplementary Note 324). For a more in-depth understanding of Eq. (2), additional detailed interpretations can be found in Method and Supplementary Materials24. We find that the anomalous score has an approximate normal distribution (Fig. 3b), which indeed reflects the typicality of momentum distribution data.

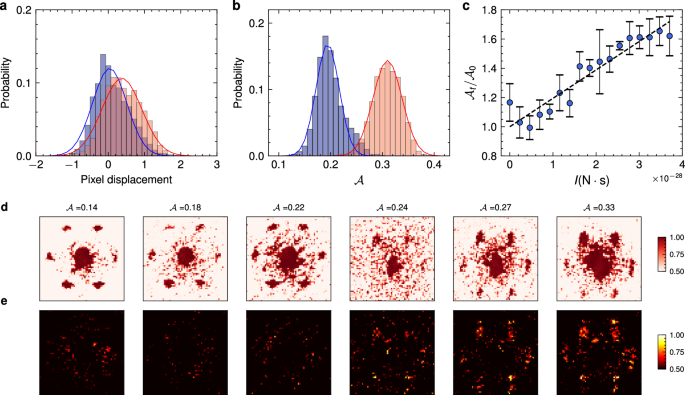

a, b The probability distribution of averaged center-of-mass (COM) momentum \({\overline{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{COM}}}}}}}}}\) (in the unit of pixels) and anomaly score \({{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}\) in the absence of force (blue) and in the presence of force (red), respectively. Noting that the pixel displacement refers to the distance between COM and the y-axis center of pixel-wise images. c.The dimensionless anomaly score as a function of impulse I = F0 ⋅ ΔT for an identical optical force F0. The normalization factor in c (\({{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{0}\)) is the averaged anomaly score in absence of the external force. The error bar in c represents one-sigma statistical uncertainty over six data points. The anomaly score \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{t}({{\Delta }}T)\) corresponds to signal-involved experiments with a force acting on the Bose-Einstein condensates for a time duration ΔT. d, e show the real time-of-flight images and their corresponding anomaly localization (see the main text), respectively. Noting that the left (right) three instances in d are sampled from datasets with force-free (force-involved) environments. More technical details can be found in Method and Supplementary Note 2 and 3.

Sensing by anomaly detection

When an external force is applied, the physical BEC system then produces TOF data n(k) of different distributions. Conventional sensing schemes examine the response in the COM momentum (Eq. (1)). The distributions of the COM momentum with and without an external force are different. Force sensing requires differentiating such distributions. When a weak force (F0 = 7.81 × 10−26N in our experiment) is applied, the distribution of COM momentum is only very weakly affected, with a barely noticeable difference from force-free distribution.

With the digital replica, namely the generative machine learning model, we compute the anomaly score \({{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}))\), a highly nonlinear function of n(k), that could incorporate higher order correlations of the data. This provides a systematic nonlinear data processing approach, much different from the linear data processing as in analyzing the simple COM momentum. As a result, the anomaly score is much sensitive to the force as it effectively reflects high-order information of the experimental data. The resultant distribution of the anomaly score caused by the weak external force is significantly different from the force-free distribution, in sharp contrast to the COM momentum (Fig. 3a). Despite the nonlinearity in the data processing, the response of the anomaly score remains to be linear to the external force (Fig. 3c).

By comparing the distributions of the COM momentum and the anomaly score, it is evident that analyzing the anomaly score, known as anomaly detection in the context of machine learning, is more efficient for detecting the external force applied to the BEC system.

We further investigate the primary characteristics that contribute to the anomaly score in presence of an external force. Specifically, we assess the momentum dependence of the residual loss, \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}}_{R}\), namely,

$${n}_{R}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})=| n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})-{G}^{* }({E}^{* }(n({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})))| ,$$

(3)

with the generator G*( ⋅ ) and the encoder E*( ⋅ ) being fixed. In Fig. 3d, we provide six representative atomic images from real experimental datasets labeled with anomaly scores. In Fig. 3e, we observe bright speckles in nR(k)(commonly referred to as anomaly localization28), with these speckles becoming increasingly prominent as the applied force intensifies. This implies the signals contributing to the force sensing mainly come from the large momentum region in the second Brillouin zone. The anomaly localization is consistent with the common understanding in the BEC community that the momentum distribution at small momenta (near zero) is more affected by interaction effects and imaging saturation artifacts, indicating the machine learning model successfully captures the relevant features of the experimental data. Further discussion on model interpretability from the perspective of feature representation28,29,30 is provided in Supplementary material24. Our findings regarding anomaly localization, exemplified by the presence of a hexagonal peak structure in the rightmost portion of Fig. 3e, imply that the dominant signal for force sensing originates primarily from high-momentum peaks observed in time-of-flight (TOF) measurements. This could be attributed to the reduced impact of various sources of noise, such as atomic scattering, trapping potential, and thermal activation, on the high-momentum components of the Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC), owing to energy separation.

Sensitivity and stability

In order to quantitatively characterize the advantage of the anomaly detection over conventional approaches, we compute the corresponding sensitivity. A general force sensing process involves a force F to be detected, and a signal q that is directly or indirectly measured in the experiment. In the previous work23, q corresponds to COM momentum \({\overline{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{COM}}}}}}}}}\) (Eq. (1)). It corresponds to the anomaly score \({{{{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}\) (Eq. (2)) in the machine learning approach reported here. The measured signals q would fluctuate in consecutive experimental measurements due to noises of various channels. We assume the fluctuations in different measurements are completely independent. The strength of the fluctuations is quantified by the standard deviation of q, to be referred to as σ0. A single measurement has a fixed time cost of T0. The minimum force we can resolve with one single-measurement is given by \({V}_{\min } \sim {\sigma }_{0}/| {\partial }_{V}q|\). Performing N times of experimental measurements, the signal to noise ratio (SNR) is given by \(\,{{\mbox{SNR}}}\,=\sqrt{N}\times | {\partial }_{V}qV| /{\sigma }_{0}\). The one-sigma sensitivity is defined as (see Supplementary Note 124)

$${{{{{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}}}}=\sqrt{{T}_{0}}\times \frac{{\sigma }_{0}}{| {\partial }_{V}q| }.$$

(4)

This definition applies to both conventional approaches and the anomaly detection.

Acting linear transformation on q, the sensitivity remains the same according to Eq. (4). However, different signals that are related by nonlinear transformations do not necessarily have the same sensitivity. We compare the sensitivities of the COM momentum and the anomaly detection approaches taking exactly the same set of experimental data. For the COM momentum approach, we obtain a sensitivity \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{S}}}}}}}}}^{{{{{{{{\rm{COM}}}}}}}}}=6.8(9)\times 1{0}^{-24}\,\,{{\mbox{N}}}/\sqrt{{{\mbox{Hz}}}\,}\) (Fig. 4a). For the anomaly detection, we have \({S}^{{{{{{{{\rm{AS}}}}}}}}}=1.7(4)\times 1{0}^{-25}\,\,{{\mbox{N}}}/\sqrt{{{\mbox{Hz}}}\,}\). This means the anomaly detection is about 40 times more sensitive than the COM momentum approach.

a The sensitivity distribution of using the anomaly score (blue), center-of-mass (COM) momentum with raw data (green) and reduced datasets (yellow), respectively. In b, the Allan Deviations σAD[δq/q0] correspond to the anomaly score (AS) and the COM momentum. The momentum difference δq = qt − q0 represents the signal response, where q0 is the force-free signal and qt is the signal corresponding to the momentum distribution produced by acting the force on Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC). Both of them decay with the integration time τ, as 1/τ. In c, we compared related works in sensitivity with force F, including measurements based on nano-tube34, nano-particles35, trapped ions with phase-coherent velocimetry31, a single trapped ion with optical clock Doppler velocimetry36, a 3D-trapped single ion18, and ultracold atoms in a cavity2. Note that error bars indicate the one-sigma statistical uncertainty in b, c.

We emphasize that in the above comparison we use the raw experimental data without invoking any prior knowledge of the physical process. The anomaly detection approach is thus entirely data-driven. We further examine how much the conventional COM momentum approach can be improved by machine learning based noise reduction. We perform Gaussian processing prior to extracting the COM momentum (see Supplementary Note 524). The resultant sensitivity can be improved to \({S}_{r}^{{{{{{{{\rm{COM}}}}}}}}}=1.6(4)\times 1{0}^{-24}\,\,{{\mbox{N}}}/\sqrt{{{\mbox{Hz}}}\,}\) (Fig. 4a). But this is still one-order-of-magnitude worse than our anomaly detection.

In Fig. 4c, we show the comparison of the achieved sensitivity of digital twinning atomic BEC with previous experiments, including phase-coherent velocimetry31, cold atoms in a cavity2, and trapped ions18. Our achieved force sensitivity shows orders-of-magnitude improvement over other experiments. It is worth to mention that the digital twinning and the anomaly detection techniques developed here are quite generic. These techniques are readily applicable to improve the sensitivity of other experimental setups as well.

For quantum force sensing, it is also important to have long-term stability besides the high sensitivity. This is captured by the Allan Deviation32, which is widely used to examine long-term drifts. We confirm that the Allan Deviation of the anomaly detection falls off with the integration time (τ) as \(1/\sqrt{\tau }\), having the same scaling as the Allan Deviation of the COM momentum (Fig. 4b). It is thus evident that no long-term drifts are induced by the nonlinear data processing in anomaly detection. The \(1/\sqrt{\tau }\) decay also implies the fluctuations of the anomaly score are mainly white noise, which justifies the above definition of sensitivity.

It is worth noting here that the sensitivity can also be enhanced by choosing the high data-quality region of the TOF measurements according to the impulse theorem, as used in a previous study23. Such analysis requires certain prior information of the force, and gives a sensitivity comparable to the present anomaly detection approach. Nonetheless, we emphasize that the anomaly detection approach is purely data driven, and is consequently more robust against long-term drifts in experiments. The improvement in the long-term stability is evident by comparing the Allan Deviation of the anomaly detection to the pervious study23. In the previous study, the Allan Deviation bends up at a time scale of τ = 104 s, whereas it keep decreasing following \(1/\sqrt{\tau }\) even at the time scale of 4 × 104 s.