Amorphous aluminum oxide is often used in protective thin films and film forms. However, it is not very understood that what happens at the atomic level of materials. Innovative experiments and machine learning have allowed an interdisciplinary team of EMPA researchers to model their failure structures with high accuracy for the first time.

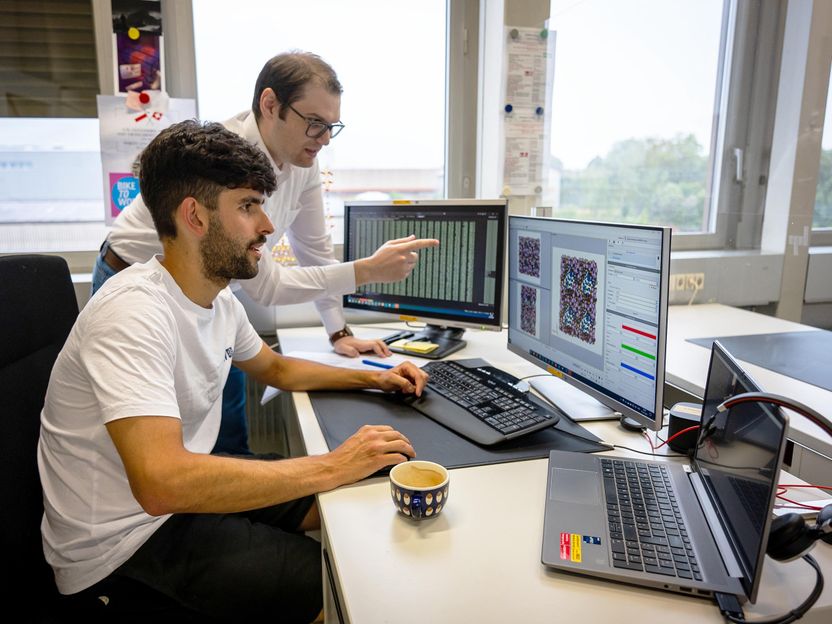

EMPA researchers led by Simon Gramatte (front) and VladySlav Turlo have been the first to succeed in simulating amorphous aluminum oxide with hydrogen inclusions with atomic accuracy.

Copyright: empa

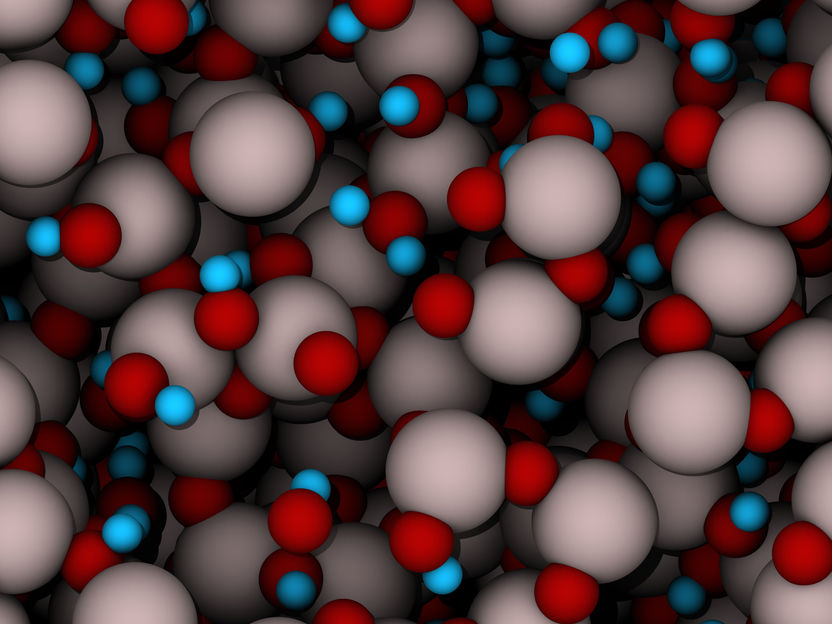

Chaotic transparency: In amorphous alumina, aluminum atoms (gray) and oxygen atoms (red) are not arranged in ordered crystal structures. The model also visualizes hydrogen atoms (blue) that are closely bound to adjacent oxygen atoms, changing the properties of the material.

Copyright: empa

EMPA researchers led by Simon Gramatte (front) and VladySlav Turlo have been the first to succeed in simulating amorphous aluminum oxide with hydrogen inclusions with atomic accuracy. Image: empa

Aluminum oxide or alumina is a fruit fry in materials science. It has been thoroughly researched and well understood. This compound, with the simple chemical formula AL2O3, frequently occurs in the Earth's crust in the form of mineral corundum and its famous color variations of sapphire and ruby, and is used for a variety of purposes, including electronics, chemical industry, and technical ceramics.

A special feature of aluminum oxide is its ability to take on a variety of structures while maintaining the same chemical composition. All of these variants are well understood – with one exception. In addition to some crystalline forms, aluminum oxide can also exist in amorphous, i.e., in a disordered state. Amorphous alumina has particularly advantageous properties for some high-tech applications, particularly in the form of a uniform protective thin film coating or ultra-thin agitating layer.

Despite its extensive use and the know-how available to handle it, amorphous alumina remains an atomic level mystery. “Crystalline materials are made up of small, periodically repeated subunits,” explains Empa Researcher VladySlav Turlo, Thun's Advanced Materials Processing Laboratory. Therefore, it is relatively easy to examine them to the level of a single atom. It's the same as modeling on a computer. After all, if you can calculate the interaction of atoms in single crystal units, you can also easily calculate a large crystal made up of many units.

Amorphous materials do not have such a periodic structure. The atoms are cluttered together – they are difficult to investigate and even more difficult to model. “When simulating a thin film coating of amorphous alumina grown from scratch at the atomic level, calculations take longer than the age of the universe,” says Turlo. However, accurate simulations are key to effective materials research. It helps researchers understand the material and optimize its properties.

Experiments satisfy the simulation

For the first time, EMPA researchers led by Turlo have managed to simulate amorphous alumina quickly, accurately and efficiently. The model, which combines experimental data, high-performance simulations, and machine learning, provides information on the atomic arrangement of the amorphous AL2O3 layers, and is the first of its kind. The researchers have published their results in the Journal NPJ Computational Materials.

A breakthrough has been made possible thanks to the interdisciplinary collaboration between the three EMPA labs. Turlo and his colleague Simon Gramatte were the first authors of the publication and are based on models based on experimental data. Materials and nanostructure mechanic researchers used atomic layer deposition to produce amorphous aluminum oxide thin films, and studied with colleagues at Duvendorf's participating technology and corrosion research.

One of the great strengths of the model is that it also takes into account the integrated hydrogen atoms, in addition to the aluminium and oxygen atoms in alumina. “Amorphous alumina contains varying amounts of hydrogen depending on the manufacturing method,” explains co-author Ivo Utke. Hydrogen, the smallest component of the periodic table, is particularly difficult to measure and model.

An innovative spectroscopy called HAXPES, which can only be achieved in Switzerland with EMPA, allowed researchers to characterize the chemical state of aluminum with various thin films, incorporate it into simulations, and for the first time reveals the distribution of hydrogen within alumina. “On top of a particular content, we were able to show that hydrogen bonds to the oxygen atoms of the material and affects the chemical state of other elements in the material,” says co-author Claudia Cancellieri. This will change the properties of the material. Aluminum oxide becomes “fluffy” and results in a lower density.

Chaotic transparency: In amorphous alumina, aluminum atoms (gray) and oxygen atoms (red) are not arranged in ordered crystal structures. The model also visualizes hydrogen atoms (blue) that are closely bound to adjacent oxygen atoms, changing the properties of the material. Image: empa

Potential breakthroughs of green hydrogen

This understanding of atomic structure paves the way for new applications of amorphous aluminum oxide. Turlo sees its greatest potential in the production of green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is produced by using renewable energy, as well as direct sunlight, to divide water. Separating hydrogen from the oxygen produced during water splitting requires an effective filter material so that only one of the gases can pass through. “Amorphous alumina is one of the most promising materials for such hydrogen films,” says Turlo. “Thanks to our model, we can better understand how the hydrogen content of a material supports the diffusion of gaseous hydrogen for other large molecules.” In the future, researchers hope to use the model to develop better films made of alumina.

“Understanding materials at the atomic level allows us to optimize the properties of materials in a more targeted way, in relation to mechanics, optics, or transmission,” says materials researcher Utke. This model could lead to improvements in all application areas of amorphous alumina. It may also be transferred to other amorphous materials over time. “We have shown that it is possible to accurately simulate amorphous materials,” Turlo summed up. And thanks to machine learning, this process only takes about a day, not billions of years.

Original Publications

Simon Gramatte, Olivier Policiano, Noel Jax, Claudia Kankerieri, Ibo Ucke, Lars PH Julgens, Vladislav Taro. “We present the hydrogen chemical state of supersaturated amorphous alumina via machine learning-driven atomic modeling.” NPJ Calculation Materials, Vol. 11, 2025-6-6

Claudia Cancellieri, Simon Gramatte, Olivier Politano, Léo Lapeyre, Fedor F. Klimashin, Krzysztof Mackosz, Ivo Utke, Zbynek Novotny, Arnold M. Muller, Christof Vockenhuber, Vladyslav Turlo, Lars PH Jeurges; “The effect of hydrogen on chemical states, stoichiometry and density of amorphous ALs.2o3 Film cultivated by deposition of thermal atomic layers”; Surface and interface analysis, Vol. 56, 2024-1-7