Framework and models

We consider sequence translation tasks (illustrated in Fig. 1a) that are ubiquitous in the study of natural language processing9,46,47. For simplicity, we assume that the sequences are bitstrings with length 4n. Such a translation task is specified by a translation rule R: {0, 1}4n × {0, 1}4n → {0, 1}, where R(x, y) = 1 means that y is a valid translation of x. The goal is to design an ML model \({\mathcal{M}}\) that takes x as input and produces a (possibly random) translation result \(y={\mathcal{M}}(x)\) with an expected success rate as high as possible. The performance can be measured by a score function \(S({\mathcal{M}})={\mathbb{E}}[R(x,{\mathcal{M}}(x))]={\mathbb{P}}[R(x,{\mathcal{M}}(x))=1]\in [0,1]\). We note that this is a fully classical ML task with no particular quantum feature, in contrast to the inherently quantum tasks of learning properties of quantum states or processes considered in refs. 22,23,24,26.

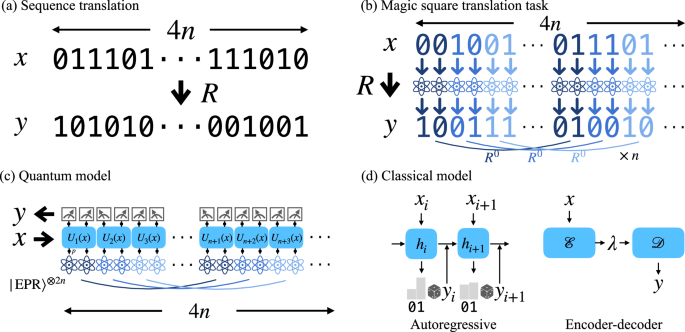

a Sequence translation task R: {0, 1}4n × {0, 1}4n → {0, 1} where R(x, y) = 1 indicates valid translation. b The magic square translation task R constructed from n parallel repetition of the sub-task R0 adopted from the Mermin-Peres magic square game. c The constant-parameter-size quantum learning model with entanglement supply. Here, \(\left\vert {\rm{EPR}}\right\rangle =(\left\vert 00\right\rangle +\left\vert 11\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) is the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) state, and qubits with the same color are entangled. d The two commonly-used classical machine learning models: autoregressive and encoder-decoder models.

As a simple example of a translation task and its corresponding rule R, consider the identity translation where every input sequence x is mapped to itself y = x. In this case, the translation rule is the Kronecker delta R(x, y) = δy,x which has value one if and only if y = x. For a random model \({\mathcal{M}}\) that generates a random translation result y uniformly sampled from {0, 1}4n regardless of the input x, its score is the probability of randomly guessing \(S({\mathcal{M}})=1/{2}^{4n}\).

Our quantum model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) for such translation tasks is a simple, parameterized shallow quantum circuit shown in Fig. 1(c). It is a quantum circuit on 4n qubits where a two-qubit unitary gate Ui(x2i−1, x2i) acts on each consecutive pair of qubits (2i − 1, 2i), ∀ 1 ≤ i ≤ 2n. After a single layer of gates, we measure the qubits in the computational basis and output the resulting bitstring y as the translation result. The initial state is independent of x, but can be prepared strategically to supply entanglement resources. Additional layers and pre-/post-processing can be added for more general purposes, but this most basic setting is enough here and straightforward for experimental realization. To accommodate variable sequence length, we apply weight sharing. That is, a common set of unitaries is used at different places of the sequence. Therefore, only a constant number of parameters is used in this quantum model.

For the classical model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{C}\), we consider the commonly used autoregressive and encoder-decoder models (Fig. 1d), also with weight sharing. In general, their communication capacity c (i.e., the amount of information about the input sequence that the model can carry and spread to other parts of the sequence) is limited by the number of parameters d of the model48. Here, we define the number of parameters more broadly as the number of bits used to store the intermediate state at each time step during the forward computation of the model. For example, the communication capacity of an autoregressive (encoder-decoder) model is proportional to the dimension of its hidden state (latent space). Based on this observation, we focus on this general family of classical models whose communication capacity is bounded by its parameter size. We call them communication-bounded classical models, which include commonly used ones, such as recurrent neural networks or Transformers49. We also allow the classical models to have shared randomness distributed across different parts of the model, as the classical analog of the shared entanglement in the quantum model. This gives commonly used classical model extra power so that we have a fair comparison between classical and quantum. Note that in defining the communication complexity, we only count the transmitted information that depends on the input sequences. Therefore, neither shared entanglement nor shared randomness counts as they are precomputed and do not depend on the inputs. More rigorous definitions and details of these classical models can be found in the Supplementary Materials Sec. I.

Quantum advantage in inference

Communication is a key bottleneck in solving natural language processing tasks. To deal with long-range context in texts, the model must be able to memorize features of previous parts of the sequence and spread the information to other parts. To overcome this bottleneck, we note that entanglement can be used to reduce the classical communication needed to solve certain distributed computation tasks44. This is achieved by allowing quantum protocols that are more general than classical ones, without direct transmission of classical information. This gives us a way to trade entanglement for advantage in sequence translation tasks.

To establish such a quantum advantage, we design an ML task that is easy for quantum computers while hard for classical ones. In particular, we design a translation rule R based on quantum pseudo-telepathy, the most extreme form of the above phenomenon, where the task can be solved by an entangled protocol with no classical communication at all. We adopt a variant of the Mermin-Peres magic square game36,50,51,52,53 as the building block of our translation task R: {0, 1}4n × {0, 1}4n → {0, 1}. In such a game, two players A, B each receive two random bits xA, xB ∈ {0, 1}2 and output two bits yA, yB ∈ {0, 1}2. Let I(x) = 2x1 + x2 ∈ {0, 1, 2, 3} and \({y}_{3}^{A}={y}_{1}^{A}\oplus {y}_{2}^{A}\oplus 1,{y}_{3}^{B}={y}_{1}^{B}\oplus {y}_{2}^{B}\), where ⊕ is the addition in the field \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\). The game is won if and only if at least one of the following is satisfied: (1) either xA or xB is 00; (2) \({y}_{I({x}^{A})}^{B}={y}_{I({x}^{B})}^{A}\). This winning condition defines a translation rule R0: {0, 1}4 × {0, 1}4 → {0, 1}. For clarity, we include a transparent illustration of this translation rule R0 in Supplementary Materials Table S2. We show that this translation task R0 cannot be solved with probability more than ω = 15/16 by any classical non-communicating strategies. Meanwhile, a quantum strategy using two Bell pairs shared between A and B can solve this task with certainty.

To boost the separation in score, we combine n parallel repetition of R0 to form the translation task R. For any x, y ∈ {0, 1}4n and 1 ≤ i ≤ n, we set the two players of the ith game to receive x2i−1x2i, x2n+2i−1x2n+2i and output the corresponding bits of y. The translation (x, y) is valid (R(x, y) = 1) when all these n sub-tasks R0 are simultaneously solved. We call this task R the magic square translation task. It can also be viewed as a non-local game with two players A, B, where they each corresponds to the first and last 2n bits of x, y. In this way, the score of any classical non-communicating strategy is reduced to 2−Ω(n)54, while that of the quantum protocol using 2n Bell pairs remains one. This allows us to prove the following theorem, which exponentially improves the logarithmic advantage in ref. 37.

Theorem 1

(Quantum advantage without noise). For the magic square translation task R: {0, 1}4n × {0, 1}4n → {0, 1}, there exists an O(1)-parameter-size quantum model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) that can achieve a score \(S({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q})=1\) using 2n Bell pairs. Meanwhile, any communication-bounded classical model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{C}\) that can achieve a score \(S({{\mathcal{M}}}_{C})\ge {2}^{-o(n)}\) must have Ω(n) parameter size.

Theorem 1 gives an unconditional constant-versus-linear separation between quantum and commonly used classical ML models, in terms of expressivity and inference speed. Here, higher expressivity means fewer parameters needed to express the target translation rule, and faster inference speed refers to less time needed to translate an input sequence. We remark that this can be straightforwardly boosted to arbitrary polynomial separation by supplying polynomially many qubits, similar to the approach exploited in ref. 40. We prove Theorem 1 by dividing the sequence into two halves and bounding the communication between the two parts required to solve the magic square translation task. We derive the score of the classical model from bounds on the success probability of non-communicating classical strategies of the magic square game54,55, and relate it to the communication capacity and the size of the classical model. To show the quantum easiness, we embed the quantum strategy of the game into the quantum model, which can win the game with certainty. See the Supplementary Materials Sec. II for technique details.

To demonstrate this quantum advantage on near-term noisy quantum devices, we show that it persists under constant-strength noise. In particular, we consider single-qubit depolarization noises, with strength p following each gate that corrupts the state ρ into \((1-p)\rho +\frac{p}{3}(X\rho X+Y\rho Y+Z\rho Z)\)3. We prove the following theorem.

Theorem 2

(Quantum advantage with noise). For any noise strength p ≤ p⋆ ≈ 0.0064, there exists a noisy magic square translation task Rp: {0, 1}4n × {0, 1}4n → {0, 1}, such that it can be solved by an O(1)-parameter-size quantum model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) under depolarization noise of strength p with score \(S({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q})\ge 1-{2}^{-\Omega (n)}\) using 2n Bell pairs. Meanwhile, any communication-bounded classical model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{C}\) that can achieve a score \(S({{\mathcal{M}}}_{C})\ge {2}^{-o(n)}\) must have Ω(n) parameter size.

We prove Theorem 2 by constructing a family of noisy magic square translation tasks Rp that are a bit easier than the original task (see the Supplementary Materials Sec. II for technical details). Instead of demanding simultaneous winning of all sub-games as in R, the noisy task Rp only requires winning a certain fraction of them. The fraction is chosen such that the task remains hard for classical models, but can tolerate mistakes caused by constant-strength noise, thereby going beyond the best known \(1/{\mathsf{poly}}(n)\) noise tolerance proved in ref. 37. This requirement leads to the noise threshold p ≤ p⋆ = 1 − (15/16)0.1 ≈ 0.0064, which can be improved by designing more sophisticated sub-tasks R0.

Quantum advantage in training

We have proven the existence of a constant-depth quantum model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) that can solve the magic square translation task near-perfectly. Next, we show that this optimal model can be found efficiently with maximum likelihood estimation using constant-size training data M = O(1) and training time T = O(1). Here, the size of the training data \({\{({x}^{(i)},{y}^{(i)})\}}_{i = 1}^{N}\) with R(x(i), y(i)) = 1 is defined as M = Θ(nN), since each data point (x(i), y(i)) is of size Θ(n). This implies that the number of data samples N required to train the quantum model scales inversely proportional to the size of the task.

Theorem 3

(Quantum advantage in training). There exists a training algorithm that, with probability at least 2/3, takes \({\{({x}^{(i)},{y}^{(i)})\}}_{i = 1}^{N}\) with size M = Θ(nN) = O(1) as input and outputs the optimal quantum model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) for the task R. Moreover, the running time of this training algorithm is T = O(1).

We prove Theorem 3 by explicitly constructing the training algorithm (in Supplementary Materials Sec. III). The algorithm performs maximal likelihood estimation by an exhaustive search over all possible sets of parameters in \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) and outputs the one with the maximal empirical likelihood calculated from the training data. We then show that N = O(1/n) number of data samples suffices to estimate the likelihood accurately enough. Combining with the fact that the quantum model only has O(1) many parameters, this gives the desired space and time complexity to train the quantum model.

In contrast, as shown in Theorems 1 and 2, any classical model requires at least Ω(n) parameters. This makes their training generally harder. In particular, if we assume that the d parameters in the model can only take K = Θ(1) discrete values (e.g., due to machine precision), then the number of possible hypothesis functions represented by the classical model is Kd. Therefore, the generalization error of the model (i.e., test loss minus training loss) is expected to be \(\sqrt{d\log K/N}\)56. This means that only when N ≥ Ω(d) ≥ Ω(n) will the statistical fluctuation be small enough such that accurate training can be guaranteed. Intuitively, this is because that the information needed to specify a model from a set of Kd possible models is \(\log ({K}^{d})=d\log K\), so the training algorithm is expected to need roughly these many samples to train well. This requirement corresponds to a training data of size M ≥ Ω(n2) and training time T ≥ Ω(n2), quadratically worse than the quantum case. Though we cannot rigorously prove that no training algorithm can do better, it gives a general expectation on the amount of training resource needed by classical models. Below, we conduct numerical experiments to empirically validate this quantum advantage in training.

Numerical and experimental results

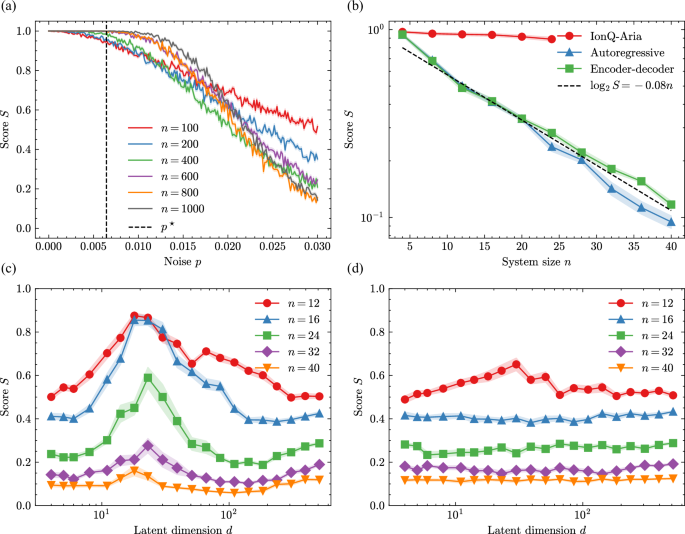

Since the optimal quantum model \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q}\) is composed of classically-controlled Clifford operations, we can simulate it efficiently on classical computers in O(n3) time57. Note that this is compatible with the proved Ω(n) lower bound. This enables us to study the noise robustness of the quantum model on up to n = 1000 qubits using PyClifford58. Note that in this section, we use n to denote the system size, which is previously denoted as 4n. For each system size n and noise level p ∈ [0, 0.03], we calculate the average score on the task Rp with 104 random inputs. The resulting scores and their standard deviations are plotted in Fig. 2(a) as solid lines and shaded areas. We observe that as the problem size n grows, a plateau of perfect score below the noise threshold p⋆ ≈ 0.0064 emerges, in accordance with the theoretical prediction \(S({{\mathcal{M}}}_{Q})\ge 1-{2}^{-\Omega (n)}\) in Theorem 2. This validates the robustness of the quantum model against constant-strength noise.

a Performance of the quantum model on the noisy magic square translation task Rp with different problem size n and noisy strength p. For each n and p, the score of the model is averaged over 104 randomly sampled inputs x, and plotted in solid lines. Shaded areas indicate standard deviations. b The quantum model executed on IonQ Aria achieves consistent high score, while the performance of classical models with d = 4 decays exponentially as the system size n grows. c,d Performance of classical autoregressive c and encoder-decoder d models on the magic sqaure translation task R with different problem size n and model size d. For each n and d, the score of the model is calculated from 103 randomly sampled test inputs x and 10 random training instances. The average scores are plotted in solid lines and the shaded areas indicate standard deviations.

For classical models, we choose the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) architecture59 as the common backbone of the autoregressive and encoder-decoder models. We adopt the standard implementation of GRU from Keras60 and tune its latent dimension d to control the model size. For each problem size n up to 40, we generate training data of size N = 104 by randomly sampling the input x, run the noiseless optimal quantum model for R, and collecting the output y. We train the model by minimizing the negative log-likelihood loss using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate 10−2 and a batch size 103 for 104 epochs. If the loss stops decreasing for 500 epochs, we terminate the training. Then we calculate the score of the model on 103 newly sampled inputs x, and average it over ten random training instances. The results are plotted in Fig. 2c, d and details of the implementation can be found in the Supplementary Materials Sec. IV.

We find that for each n, the score of each classical model first increases as the latent dimension grows. Then it reaches a peak at d ~30 and starts to decrease. The scores at small and large d are roughly the same, which decreases exponentially with n, as shown in Fig. 2b to be around \(S({{\mathcal{M}}}_{C})\approx {2}^{-0.08n}\) for fixed d = 4, confirming the prediction in Theorem 1. This phenomenon comes from the delicate dilemma due to insufficient communication capacity at small d and overfitting at large d. At small d, the communication capacity of the model increases with the size d, allowing the model to capture contextual information with longer range. However, when d is large and surpasses the control of N, the limited sample size N cannot provide enough information to train the model well. This overfitting issue causes the performance of the model on newly sampled test data to decrease again. This explanation is confirmed by the large generalization error observed when d ≳ 100. The constant-versus-linear separation together with the overfitting problem makes the quantum advantage already evident at a relative small system size n ~ 40.

To better demonstrate this noise-robust quantum advantage, we carry out experiments on IonQ’s 25-qubit trapped-ion quantum device Aria via Amazon Web Services. We execute the quantum model to generate 103 random translation results on up to 24 qubits and calculate its average score on the task Rp with fraction threshold set to 0.95. The results are plotted in Fig. 2b and calibration details are provided in Supplementary Materials Sec. IV. We find that the scores achieved on current quantum devices are consistently above 0.88 for up to problem size n = 24. When compared to the performance of classical models, we observe a clear exponential quantum advantage in score. Given that the noise strength in IonQ Aria is not yet below p⋆, we expect that the performance of the quantum model will improve with smaller noise and larger system size according to Theorem 2.

We note that the performance of autoregressive models are in general better than encoder-decoder models. Their peaks of score are sharper and appear at smaller d. This is because that autoregressive models have smaller communication burdens as they do not need to memorize the whole input with their hidden states. In contrast, for encoder-decoder models, the d required for communication quickly grows and falls into the overfitting regime, causing the peaks to disappear when n is large.