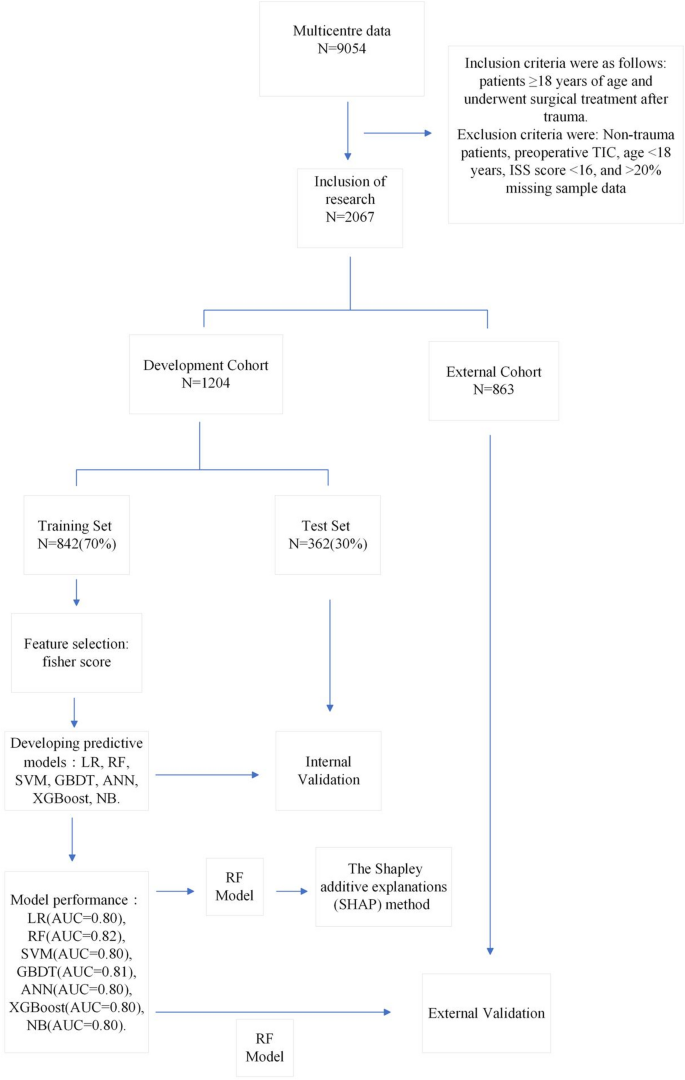

Initially, the study included 9,054 cases. After excluding non-traumatic patients (n= 8), people with preoperative coagulopathy (n= 35), under 18 years old (n= 5), ISS score <16 (n= 6850) and if more than 20% of sample variables are missing (n= 89), a total of 2067 cases were included in the study, as shown in Figure 1.

Patient selection and data set segmentation flow chart.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the development cohort, with median age of 51 (38–61) and 314 males (26.1%). The overall incidence of TIC was 25.4%. There were no significant differences between the two groups between the demographics and preoperative comorbidities (p>0.05); however, there were significant differences in injury, preoperative condition (shock, emergency surgery, ISS, ASA, heart rate), preoperative intervention (hemostatic drugs, endotracheal intubation, vasoactive drugs), intraoperative intervention (anaesthetic modality, anesthesia modality, bicarbonate, angiographic drugs, closed drugs, at-time, at-time, breast intervention, intraoperative intervention (intraoperative intervention). Plasma, crystal tip, colloid, temperature), and preoperative tests (WBC, PLT, NEU, NEU%, RDW, MPV, urea, CR, calcium, albumin, albumin, globulin, ALT, APTT, PT, INR, and FIB) (p<0.05).

Table 2 shows baseline characteristics and externally validated data for the development cohort. The incidence of postoperative TIC was 25.4% (306/1204) in the development cohort and 2.9% (25/863) in the external validation data. Variables that showed significant differences (p<0.05) Two cohorts included injuries status (mechanism of injury, location of injury) preoperative factors (impact, emergency, ASA classification, ISS, heart rate), preoperative intervention (intervention procedure, transfusion, hemostasis, tracheal intuition, vasopressor), Neu%, RBC, RBC, HGB, HCB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, HGB, RDW, PDW, MPV, CR, sodium, potassium, calcium, albumin, globulin, TBIL, AST, APTT, PT, INR, FIB), intraoperative intervention (type of anesthesia, sodium bicarbonate, intraoperative baso bone type, narcotic plant drugs, narcotic disorders, narcotic paralysis, narcotic obstacles, crystal edges, colloids, urine output, intraoperative temperature), tic. Table 3 shows one-way analysis of training and test sets. The results show that there is no significant difference between all variables between the two groups (p> 0.05).

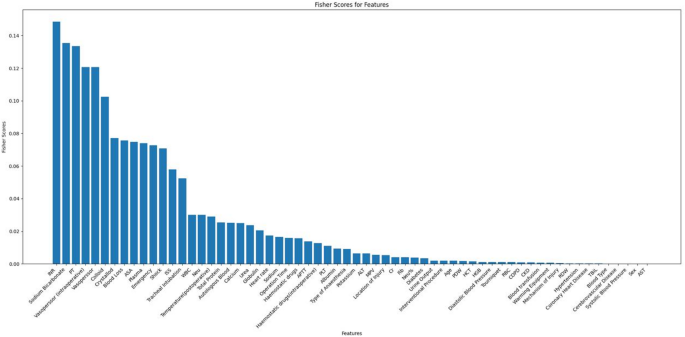

Figure 2 shows the Fisher scores in descending order, in descending order, aiding in selecting the optimal subset of the features of the seven models. Finally, the top 32 variables were selected for model training.

Ranking of Fisher scores for 62 features.

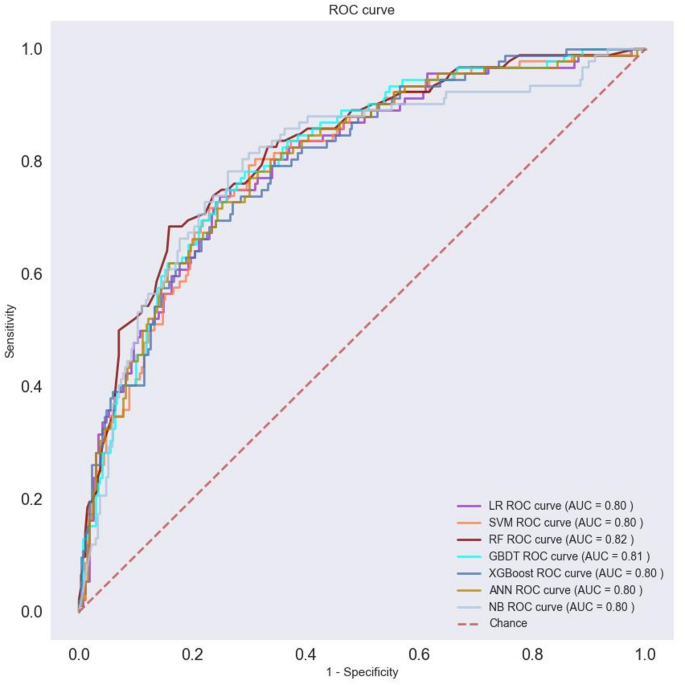

To assess the performance of the machine learning model, the data were divided into training and test sections at a 7:3 ratio, and 5x cross-validation was performed. Table 4 summarizes the results of model evaluations. Additionally, the ROC curves for visual comparisons are shown in Figure 3.

ROCs of seven machine learning models.

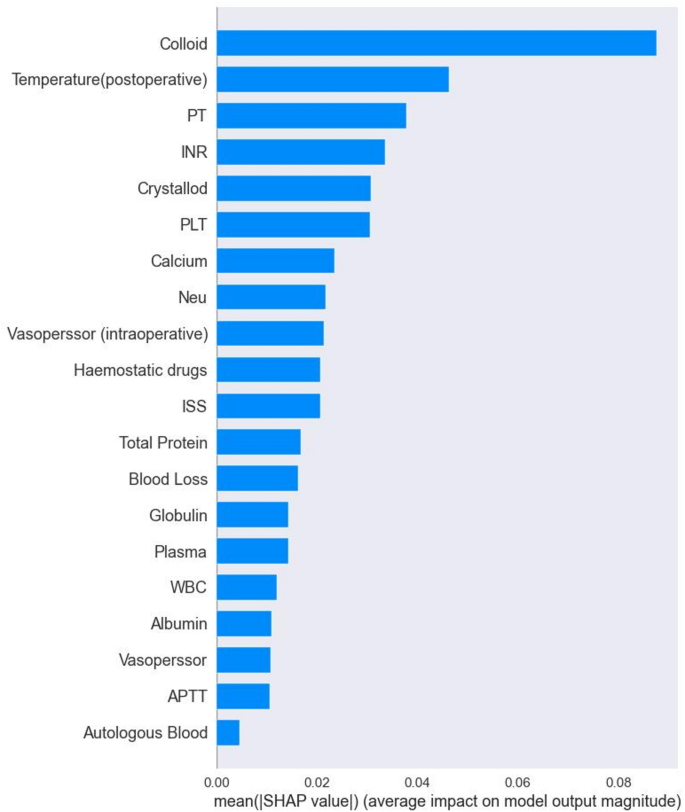

We evaluate the performance of the model with AUC, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. The selected RF machine learning models after evaluation were used to analyze risk factors for postoperative TIC in trauma patients. This analysis was based on the importance of built-in features and the results of SHAP analysis, which aimed to construct a predictive model for postoperative TIC risk. Figure 4 shows the top 20 features and their importance according to the built-in functional analysis of the RF model. Key risk factors identified include colloids, temperature (postoperative), PT, INR, crystalline edge, PLT, calcium, and vascular disorders [intraoperative]hemostasis.

Ranking of importance of TIC features in RF models.

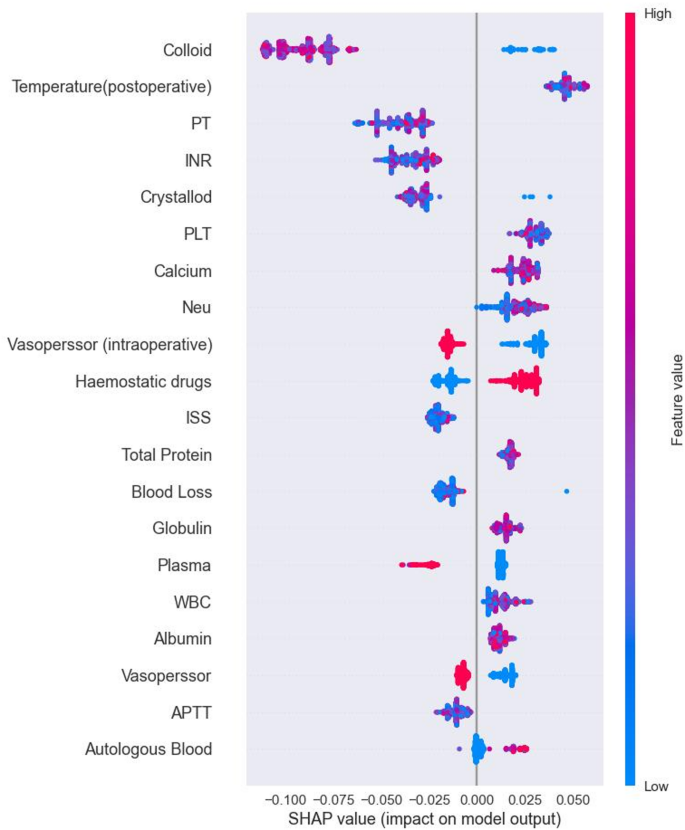

Shap is a tool used to interpret predictions in machine learning models by visualizing the contribution of each feature. It provides insight into both the direction and magnitude of the impact of each feature on model prediction. Figure 5 shows a summary plot of the SHAP analysis of the RF model, highlighting the positive and negative contributions of features to predict postoperative TICs in trauma patients. By examining the distribution of SHAP values, we identify features that have a significant impact on the results of the prediction. For example, a higher colloid SHAP value has a greater impact on predicting TIC risk. The red distribution implies samples with high feature values, which correlates positively with the prediction results, suggesting a high risk of TIC. Conversely, the blue distribution shows samples with lower feature values, which negatively affect predictions and indicate a lower risk of TIC.

Summary plot of SHAP values based on the RF model.

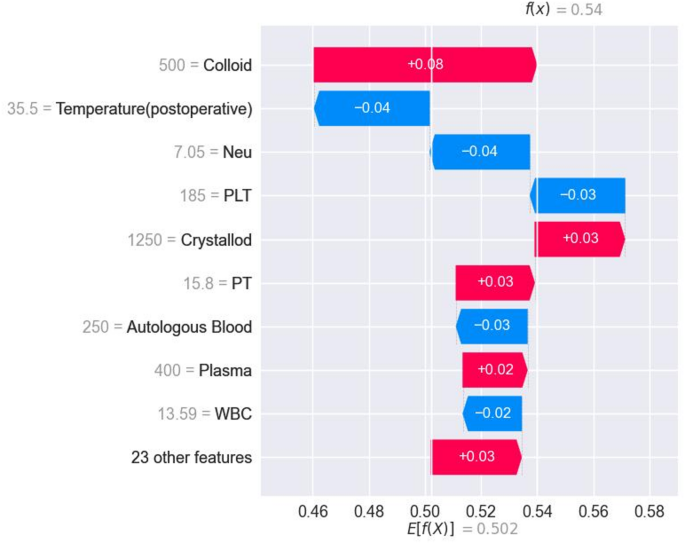

Figure 6 shows a SHAP-specific instance plot, detailing how each feature affects TIC predictions for individual samples along with predicted values. This helps to assess each patient's risk for postoperative TIC.

SHAP force plots of predictive scores of postoperative TIC risk in severe traumatic patients corresponding to specific cases.

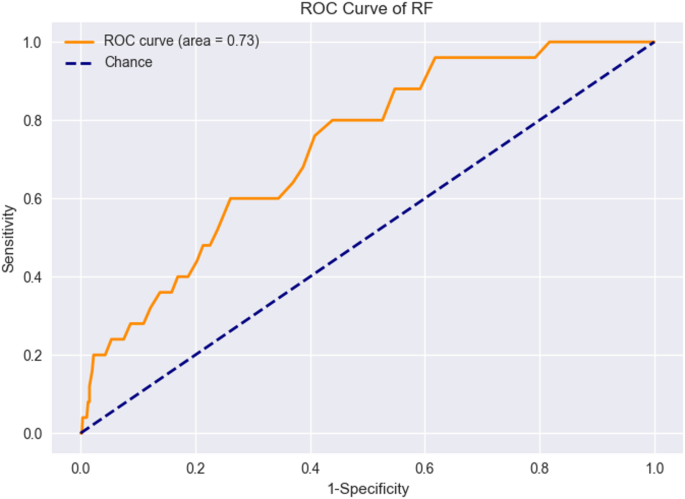

For external verification, 4594 samples were collected from three additional centers. After applying exclusion criteria, 863 patient samples formed an external validation set. Previously trained RF models were applied to this set, bringing an AUC value to 0.73. Figure 7 shows the ROC curve for external validation. Table 5 shows the performance of the RF model in external validation.

ROC curves for external verification of RF models.