detail

When AI meets reality: Hard real-world lessons in modern app delivery

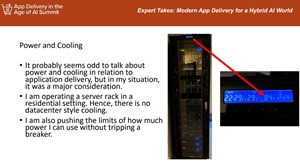

At today’s Online Technology Education Summit, Virtualization and cloud reviewIn , longtime author/presenter Brien Posey used actual real-world buildouts of three custom applications, including two AI-enabled apps, to illustrate what “app delivery” looks like beyond build pipelines and deployment mechanisms. Rather than presenting a theoretical model, Posey structured the session around lessons learned while building, deploying, and operating applications in his own environment.

This session, titled “Expert Takes: Modern App Delivery for a Hybrid AI World,” is available for on-demand replay thanks to our sponsor A10 Networks.

“So I think the biggest lesson is to expect everything to take longer than expected when it comes to building, deploying, and hosting custom applications.”

Brien Posey, 22-time Microsoft MVP

This presentation was part of the broader App Delivery in the Age of AI summit, which explores how AI is changing the way applications are built, delivered, and scaled across hybrid environments. Sessions focused on modern delivery pipelines, performance and reliability considerations, and the practical implications of introducing AI-driven components into new and existing applications, with an emphasis on approaches that enable teams to move faster without losing operational control.

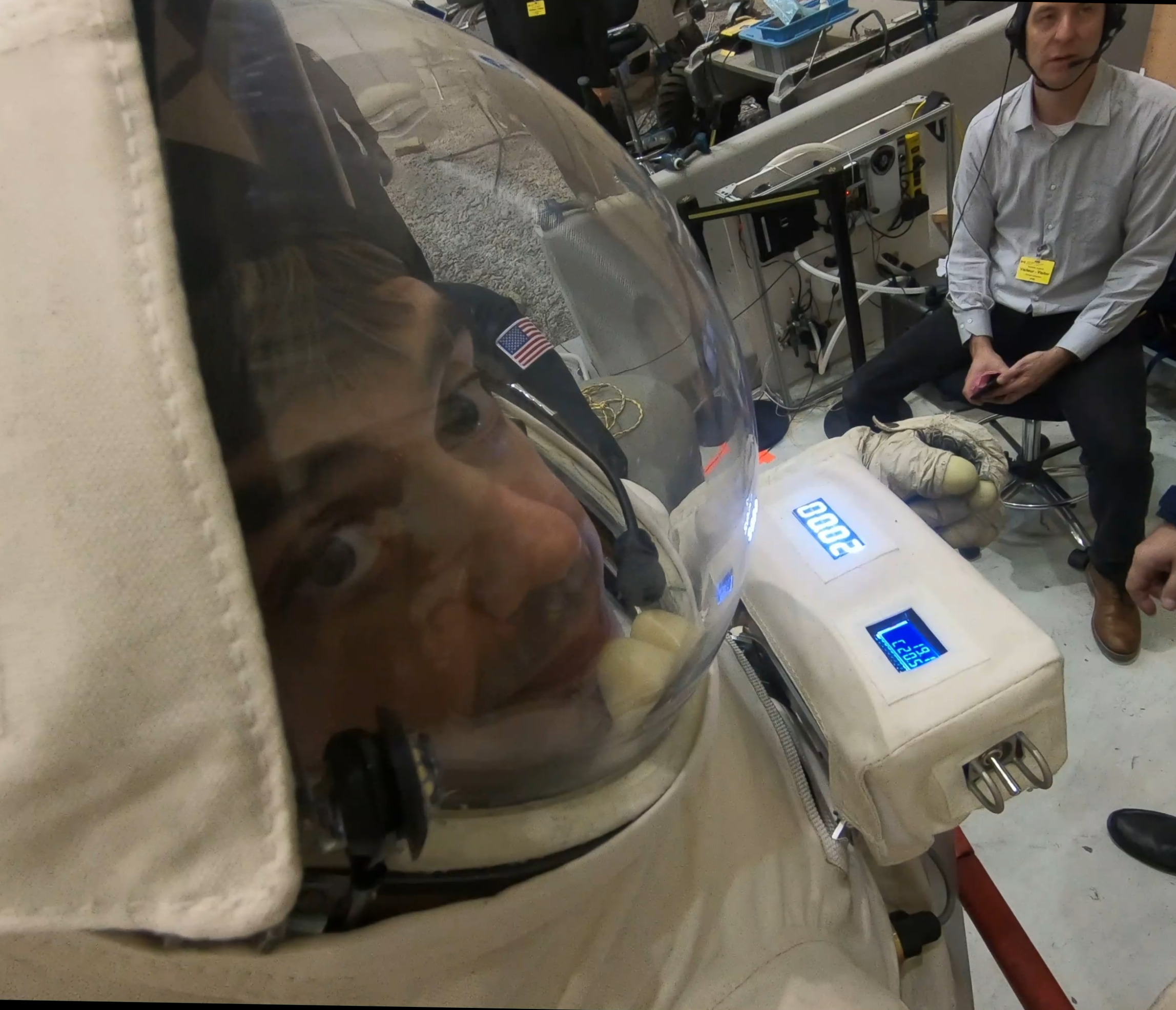

GPU Reality meets Hyper-V constraints

Posey said that while application delivery ranges from build to long-term maintenance, “careful planning and attention to detail are non-negotiables.” For his AI-enabled application, the planning pressure point was the GPU. The app required hardware acceleration. This forced him to make decisions that not only affected performance, but also where and how he could run his workloads.

His initial design was simple. Install a GPU on a Hyper-V host and use discrete device allocation to connect it to a VM and run your AI workloads there. In evaluating that plan, we encountered constraints that made the approach impractical for our scenario. One limitation is that “you can only map a GPU to a single virtual machine unless you partition it,” he noted, which may not be suitable for AI workloads that benefit from full access to GPU resources.

We also discussed how binding VMs to physical GPUs impacts operational flexibility in ways that are often overlooked during initial planning. “When you bind a virtual machine to a physical GPU, at least in Hyper V, you lose the ability to live migrate that application,” he said, adding that replication and failover planning becomes more complex if the target host does not have an equivalent GPU mapping.

Hardware practicalities further complicated the design constraints. Posey uses a 1U server and explained that “it’s hard to find GPUs that fit into a 1U server.” Even when a physically compatible card was found, power delivery and vendor support details became obstacles, and checking server hardware compatibility guidance for supported GPUs narrowed the choices even further.

Taken together, these constraints forced Posey to abandon his initial assumption that “putting a GPU on the host and passing it through” was a clean solution for AI app delivery. In his case, the GPU decision became the application delivery decision. This is because the GPU decision shaped the architecture, operational model, and set of platform features that he could actually rely on.

Avoid GPU, power, and cooling limitations

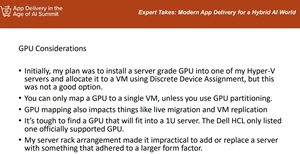

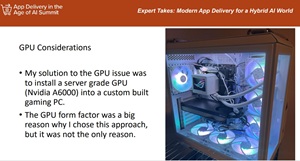

With traditional server-based GPU options exhausted, Posey took an unconventional approach to keeping AI workloads viable. Rather than forcing GPUs into existing server infrastructure, he moved the AI acceleration layer completely out of the rack.

His solution was to install a server-grade Nvidia A6000 GPU into a custom-built PC. This is primarily an approach driven by physical constraints. The larger chassis eliminates the form factor limitations encountered with 1U servers, while also providing more flexibility in terms of power delivery and cooling.

These factors were important because Posey operates infrastructure in a residential environment. “We’re running server racks in a residential environment,” he said, noting that they don’t have data center-style cooling and are “pushing the limits of how much power we can use without tripping the circuit breaker.” By moving the GPU workload to another system, we were able to physically relocate heat and power consumption away from the main rack.

Although the gaming PC approach solved some immediate problems, Posey emphasized that it introduced new trade-offs. Unlike server hardware, the system lacked redundant power supplies and error-correcting memory, making it a potential single point of failure. Operating system selection also became part of the delivery discussion.

Posey initially ran Windows 11 on its systems to cut costs, but eventually moved to Linux. The AI application itself will still run on Windows, but the Linux system will host GPU-dependent components. “These are components that require direct access to the GPU, rather than the application itself,” he said.

This split architecture allowed us to maintain our existing application design while addressing the operational realities of AI workloads. We also highlighted how application delivery decisions go far beyond code and pipelines to incorporate hardware design, operating system selection, and environmental constraints that are not visible in abstract delivery models.

Cross-platform access forces you to rethink application delivery

Shortly after stabilizing its AI infrastructure, Posey encountered another unexpected change. That is, his environment is no longer limited to Windows. His custom applications were written for Windows, but with the growing presence of Linux and macOS systems, he had to rethink how he accessed these applications.

Since 1993, Posey said he had only used Windows, but changing circumstances led him to add Linux systems and MacBooks to his network. This change required decisions about whether applications should be Windows-only or accessible across platforms.

Posey discussed the options they evaluated for cross-platform delivery, starting with native rewrites. Refactoring an application for multiple operating systems requires maintaining parallel versions of the codebase, but that level of effort is impractical, he said. Refactoring the application to a web-based system was more future-proof, but required taking the mission-critical application offline during redevelopment.

Other alternatives included compatibility layers such as Wine, virtualization approaches, and dual-boot configurations. Posey said some options have compatibility inconsistencies and others have performance or licensing shortcomings that make them unsuitable for everyday use.