Architecture and performance of MIC

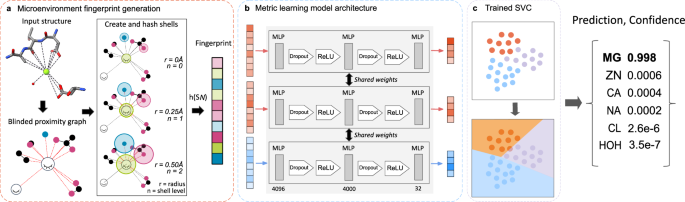

The MIC tool assigns labels to waters and ions modeled in PDB structures, identified from spherical features in cryo-EM and x-ray crystallography maps. The overall workflow consists of three steps: (1) generating the fingerprint representation for the chemical environment surrounding the site, (2) condensing this representation into a lower-dimensional embedding using a trained deep metric model, and (3) passing this embedding through a support vector classifier (SVC)56 to obtain final probabilities for all classes as well as prediction confidence (Fig. 1). The combination of these techniques enables us to achieve models that are accurate despite relatively small dataset sizes as well as probe the models’ learned embedding space to determine the salient features that differentiate between classes.

MIC is a multi-step ML workflow for classifying experimental water and ion sites. a Ion fingerprints are generated by first constructing a proximal interaction graph containing all atoms within 6 Å for the density of interest. The fingerprint generation protocol iteratively captures local chemical information by hashing the atomic invariants and interactions within consecutive shells originating from each atom. The example structure shown here is 4KU4:A:Mg:302. b The fingerprints are embedded into a lower-dimensional embedding space by a metric learning model consisting of a 4096-dimensional input layer, a single hidden layer with 4000 neurons, and an output layer of 32. ReLU is an activation function \(f(x)=\max(x,0)\). c The final step of MIC is using an SVC on the generated fingerprints to output probabilities for each class. The class with the highest probability is taken as the predicted label.

Prior approaches to conceptually similar tasks have used voxel representations as input to neural networks, necessitating large 3D-convolutional architectures that are both orientation-dependent and rely on abundant training data to properly tune without overfitting33,34. Due to the stringent data filtering critical to ensure a high-quality training set of ion and water sites (see “Methods”, Supplementary Fig. 1a), we turned to alternative approaches to overcome these limitations. First, to represent each density, we use a modified version of the LUNA toolkit developed to calculate intermolecular interactions at protein-ligand interfaces and encode them into a fixed-length vector representation known as a fingerprint. This greatly reduces the size of our models while meaningfully capturing information required for downstream classification, a critical advantage due to filtering during dataset curation (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The generation process for these ion fingerprints is closely related to interface fingerprints with a few key exceptions (Fig. 1a). A proximity graph is constructed comprising all atoms < 6 Å from the center of mass of the ion or water of interest. Each atom in this graph is assigned a set of atomic identifiers depending on its chemical identity and user-selected fingerprint type (Supplementary Table 1). Crucially, we replace the initial feature vector of both the ion/water site itself and any additional waters or ions in the graph with a vector of zeros, resulting in a ‘null shell’ for each ion and any nearby waters. This step effectively blinds the representation to any existing label to protect against data leakage during downstream prediction. The final list of modified atomic identifiers and all interactions are passed through a distance-dependent hash function that converts these input features into numeric values, which are folded down to 4096 dimensions following standard molecular fingerprinting procedures35,46.

Second, these fingerprints are further condensed using a deep metric model. This model, constructed as a small feed-forward network, is trained to learn low-dimensional embeddings that maximize the distance between members of different classes (Fig. 1b). This step establishes the discriminative capabilities of the model, enabling accurate differentiation between sites belonging to similar ions. The final predictions are generated by an SVC that uses these learned latent embeddings to calculate a probability for each class, the maximum of which is taken as the label (Fig. 1c). SVC was selected as the final classification step due to consistently high performance compared to other evaluated methods (Supplementary Fig. 2j). Full details for fingerprint generation and model training are provided in Methods, and the full list of sites used for training and testing are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

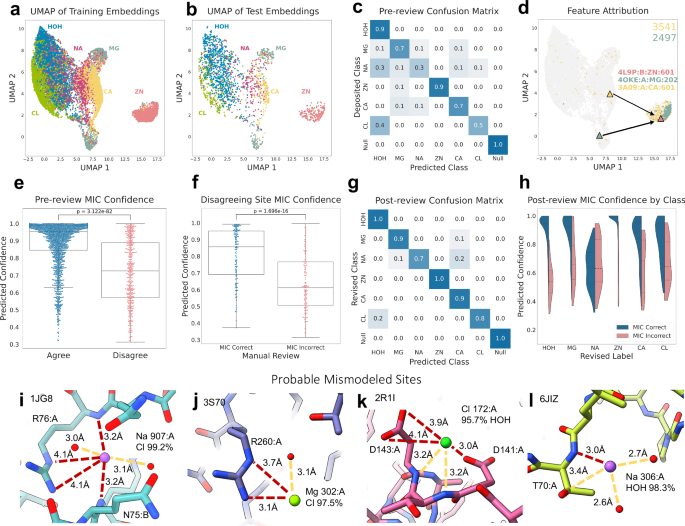

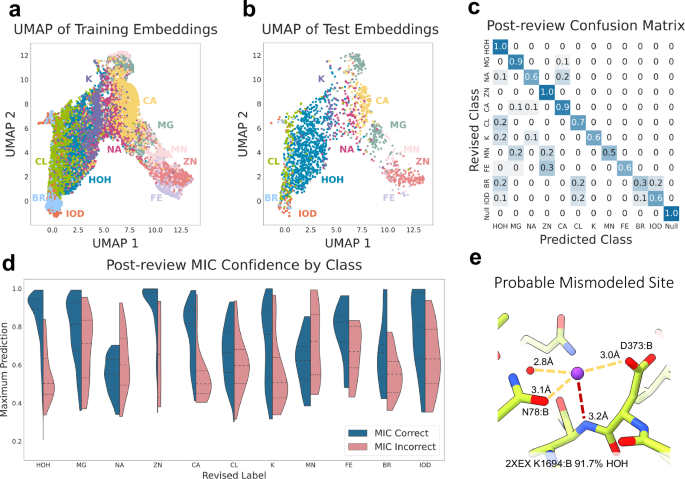

In Fig. 2, we present the performance of the MIC protocol trained on the six most prevalent classes from our curation of the Protein Data Bank: water, magnesium, sodium, zinc, calcium, and chloride. We also include a ‘null’ class, representing sites with no proximal protein atoms. The model achieves an initial accuracy of 78.6% on a held-out test set and displays notable trends in performance by class, specifically showing high accuracy for zinc, magnesium, calcium, and water recovery. (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 2). A particularly interesting property of these learned embeddings is the organization by charge, visualized here with uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP)57 and confirmed by both principal component analysis (PCA)58 and the learned latent embedding distances (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2e–g). This constraint was not explicitly included in the representation or loss function during training, and the model was provided with no information about class relationships. Rather, this is an emergent learned quality of the transition of the chemical microenvironment of the sites themselves. The model’s ability to learn the underlying structure inherent to the dataset supports the utility of our representation in capturing relevant information. We found that, despite the relatively narrow shells used in the construction of our site representation, our model proves largely robust to slight changes (≤ 0.5 Å) in ion position while maintaining confidence (Supplementary Fig. 2k, l). In addition, this reasonably organized continuous landscape also allows for confidence estimation through proximity to the classifier decision boundary, discussed below.

a, b UMAP visualization of training and test set embeddings from the MIC prevalent set model, colored by deposited class: water (blue), zinc (pink), magnesium (teal-grey), sodium (magenta), calcium (yellow), and chlorine (green). c Confusion matrix of the deposited labels and MIC predicted labels for the test set. d UMAP visualization of training set embeddings, colored by the value of the bits 2497 (green) and 3541 (yellow), corresponding to the presence of a cysteine sulfur and imidazole nitrogen, respectively. The triangles indicate the position of specific examples used to perform feature attribution: 4OKE:A:Mg:202 (green), 3A09:A:Ca:601 (yellow), and 4L9P:B:Zn:601 (pink). e, f Box-plot comparisons of MIC confidence values for various subsets of test examples. Median is denoted as a black bar, the box shows the interquartile range (IQR), and whiskers show \(\pm 1.5\times {IQR}\). P-values were calculated using the one-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test. e MIC test predictions that agree (blue, n = 1730) vs disagree (pink, n = 471) with the deposited label. f Manually inspected disagreeing examples with accurate (blue, n = 142) vs inaccurate (pink, n = 153) MIC-predicted labels. g Confusion matrix of revised labels and MIC predictions following manual review of disagreeing test examples. h Violin plots of the confidence of correct (blue) vs incorrect (pink) MIC test set predictions, split by class. i–l Examples of disagreeing annotations with probable mismodeling. i Sodium in 1JG8 corrected to a chloride, 99.2% confidence. j Magnesium in 3S70 corrected to chloride, 97.5% confidence. k Chloride in 2R1I corrected to water, 95.7% confidence. l Sodium in 6JIZ corrected to water, 98.3% confidence. Red dashed lines depict unfavorable interactions in the originally modeled structure.

One drawback to most machine learning-based approaches is a lack of interpretability of the resulting models, also known as the black box problem. An advantage of the MIC metric learning architecture is the ability to address this question and provide further validation of the model through pairwise feature attribution with integrated gradients, a technique used to quantify the importance of input features to the model’s output59,60. By calculating the attribution of fingerprints near the centroid of an ion cluster in embedding space, we can form hypotheses about which bits in the input fingerprint are most salient for a given class. Furthermore, we can use LUNA to trace back these features to their origin in the input structure’s atoms or interactions, allowing us to support the predictions with a biophysical rationale (The full details of the feature attribution protocol, as implemented by L. Ponzoni, PhD, are provided in the Methods section).

To investigate the model’s rationale behind the emergent organization by chemical microenvironment in the embedding space, we used pairwise attribution to probe the features most useful to the model for differentiating between closely related classes. Comparing two representative zinc and magnesium fingerprints (4L9P:B:ZN:601 and 4OKE:A:MG:202, Supplementary Fig. 2m, n) provides insight into how the model separates these embeddings despite similar charges. The nearby Cys367 sulfur appears in the top features by importance for zinc when compared against magnesium, along with the short distance to the Asp365 sidechain carboxylate group (Supplementary Data 3). Visualizing the embedding space by the value of the corresponding fingerprint bit (2497) shows strong localization in the zinc cluster, following known properties of zinc binding sites and likely contributing to the high confidence prediction for this example (Fig. 2d)61. Conversely, our analysis showed that salient features for magnesium similarly prioritized the slightly longer distances of nearby carboxylates (Asp6, Glu8) and the number of nearby waters, commonly observed features of magnesium sites62. Comparing this same zinc against a calcium example (3BMV:CA:A:684, Supplementary Fig. 2o) also yields known important features. In addition to the Cys367 and Asp365 recovered against magnesium, the attribution value of bit 3541 corresponding to the nearby His433 imidazole nitrogen is higher, indicating additional importance of this feature for the model in distinguishing calcium and zinc examples (Fig. 2d). In comparing the calcium and magnesium fingerprints, both assign high attribution to oxygens in their top features, but calcium includes backbone carbonyl oxygens while magnesium again includes the Asp6 carboxyl and the AMP phosphate oxygen, agreeing with known properties of these sites62,63. Interestingly, one feature that consistently returned high attribution was the null shell corresponding to the ion itself and any proximal waters and ions. The magnitude of the value at this index is consistently high and indicates the number of total sites encoded in the representation, a feature that is evidently useful to the model in structuring the learned latent space.

In addition to predicting the identity of a site, MIC provides a measure of confidence through the probability estimates output by the SVC. Because the latent representation transitions smoothly between chemically related classes, we can use the proximity to the decision boundary to measure confidence in a given prediction. We found that confidence correlated well with accuracy, suggesting a well-calibrated model. 85.5% of high-confidence predictions (> 0.7) agreed with the provided PDB label compared to 49.4% of predictions with confidence below this threshold. This metric should further assist the user in reviewing predictions by highlighting sites that may require additional manual inspection while still providing a reasonable guess as to the true identity of the ion (p-value < 1e−10, Cohen’s d = 1.04, Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 3). This property encouraged us to further investigate these high-confidence, disagreeing examples from the test set.

Manual inspection of disagreeing sites

Following model prediction, we manually reviewed 471 disagreeing test examples and considered what the correct label should be based upon several factors including favorable/unfavorable interactions, experimental map agreement (x-ray structures were re-refined with the alternative density and Fo-Fc maps were inspected in both cases), and coordination geometric features (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Data 2). We assigned each structure a score between − 3 and 3, with increasingly positive scores denoting more support for the MIC prediction and increasingly negative scores support for the original label. We identified 142 sites where we believe the provided label in the PDB to be incorrect and MIC accurate in its assignment, and 153 sites where MIC is likely incorrect and the deposited label is correct. A further 115 sites were scored as 0, reflecting that even after manual inspection and re-refinement, it was unclear which of the two labels were correct. 59 sites were also labeled as having unusual issues that would prevent proper prediction, including extended densities indicating the site represents a larger chemical entity than an ion or water, extensive heterogeneity and/or partial occupancy, the presence of an unusual multi-ion cluster, or that the likely correct identity of the ion did not fall within the set of predicted ions; these were indicated by a manual label of 30 (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). In the manually annotated cases where the MIC assignment was correct over the deposited label, the average confidence was 81.1 ± 15.8%, while the confirmed incorrect MIC predictions had an average confidence of 63.5 ± 17.0% (Fig. 2f). The revised overall test set accuracy following manual annotation is 92.4% with an average confidence of 88.4 ± 14.3% for correct predictions (Fig. 2g). The most common corrections made by MIC were reassigning spurious sodium and chloride ions to water (59 and 19 examples, respectively), followed by reassigning sodium to chloride (11 examples) and calcium to magnesium (10 examples) (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Given that 76 of the 258 total sodium sites in the test set were changed upon manual review, we speculate that approximately 20% of the sodium in the PDB may instead be water and up to 30% of all sodium in the PDB could be misannotated. Manually reviewing these examples additionally allowed us to provide an estimated accuracy cutoff by confidence (Fig. 2h). With the exception of sodium, the confidence of correctly predicted examples from each class was significantly higher (p-value < 1e-5, Cohen’s d > 1, Supplementary Table 3) than mispredicted examples. Sodium remains challenging to predict confidently, likely due to the modest quality of annotated sodium ions in the dataset, and these predictions often require additional inspection.

Four diverse examples of high-confidence probable mismodeling captured by MIC are presented in Fig. 2i–l, showing a sodium to chloride (PDB:1JG8), magnesium to chloride (PDB:3S70), chloride to water (PDB:2RL1), and sodium to water (PDB:6JIZ) substitution. In each case, there is at least one short-range (3.0–3.2 Å) unfavorable interaction, and often several modest-range (3.5–4.0 Å) unfavorable charge interactions, while lacking any opposite charge/partial charge interactions that would support the original assignment (for example, carbonyl interactions with a cation). None of the three deposited cations has the extended coordination shell or short coordination distances one would expect of a cation. Further, typically, the experimental difference maps were improved upon re-refinement with the MIC ion (Supplementary Fig. 3f, g), providing additional support for the corrected label.

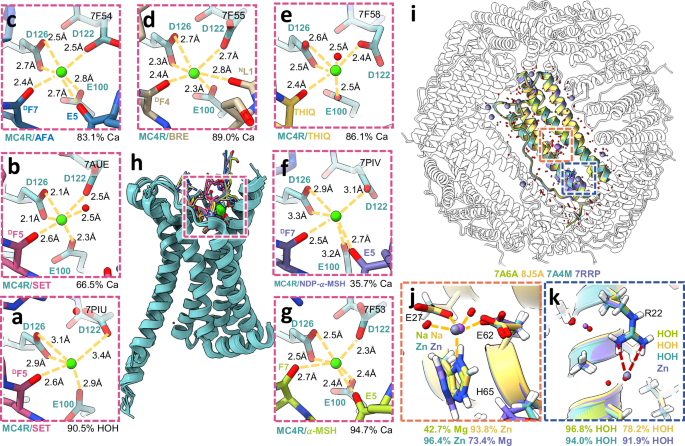

Validation of MIC on structures derived from cryo-EM maps

As all but 9 structures in the training set derive from x-ray crystallography, we wanted to examine how well MIC would work on cryo-EM structures. For this purpose, we examined two disparate cases, representing the lower bound of resolution where an ion can still be resolved in a cryo-EM map (structures of melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R) with bound calcium, nominal reported resolutions ranging from 2.6 Å to 3.1 Å) and the upper bound of resolutions currently possible with cryo-EM (apoferritin, 1.15–1.27 Å nominal resolution). In the first case, three different groups have determined several structures of MC4R bound to various ligands, resolving in each a spherical feature in the map thought by all three groups to be the calcium that has been biochemically demonstrated to be necessary for MC4R ligand binding64,65,66,67. Further, some of the structures also resolve water molecules, providing additional coordination for calcium ion binding. In the single structure from Israeli et al.64 of MC4R bound to setmelanotide (PDB:7AUE, Fig. 3b), MIC correctly identified calcium with 66.5% confidence, followed by sodium with 17.2% and magnesium with 10.5% confidence. In contrast, in the only other structure with an identical ligand, PDB:7PIU65 (Fig. 3a), the site was predicted to be water with high confidence (90.5%), with 5.0% for sodium as the second highest prediction. This likely stems from the unexpectedly long carboxylate-calcium interaction distances modeled (Fig. 3a), which at 2.9-3.4 Å are substantially longer than the ~ 2.4 Å average one would expect for a carboxylate-calcium interaction14. These coordination distances are similar to those of the other structure from Heyder et al., PDB:7PIV65 (Fig. 3f), which MIC correctly predicted to be a low confidence calcium (35.7%) and an almost identical probability of being sodium (35.2%), with the improved classification likely due to the presence of an additional carbonyl interaction. All four structures from Zhang et al.66 (PDB:7F53, 7F54, 7F55, 7F58; Fig. 3g, c–e) are predicted to have a calcium ion at this site with high confidence (94.7%, 83.1%, 89.0%, 86.1%). Given the biochemical demonstration in Yu et al.67 that this is the site responsible for the calcium-dependence of ligand binding, all structures almost certainly did make the correct assignment as calcium, a result typically correctly predicted by MIC. In the case of 7PIV and particularly 7PIU, the discrepancy can be attributed to unusual coordination modeling, which is not unexpected in the ~ 2.5–3.0 Å nominal resolution range where ions can begin to be resolved but precise placement of sidechain atoms remains challenging. Thus, MIC in this resolution range also provides some level of audit on the overall modeling of the ion/water coordination site.

a–h MC4R Ca2+-coordination site (magenta) in complex with various ligands: setmelanotide (SET, a, b), afamelanotide (AFA, c), bremelanotide (BRE, d), THIQ (e), NDP-α-MSH (f), and α-MSH (g). i–k Superimposed ion coordination sites (orange: zinc, navy: water) in four apoferritin structures: 7A4M (green), 7RRP (purple), 7A6A (teal), 8J5A (yellow). j For three structures, the ion is predicted to be zinc with confidence exceeding 70%. The 7RRP outwardly turned histidine imidazole shifts the prediction from zinc to a high-confidence magnesium. k Superimposed ion coordination site in four apoferritin structures: 7A4M (green), 7RRP (purple), 7A6A (teal), 8J5A (yellow). An additional site is shown in the top left, assigned sodium in 7RRP and water in all other structures.

On the other end of the resolution spectrum are the atomic-resolution structures of apoferritin determined by several labs68,69,70,71, generally producing quite superimposable structures (Fig. 3i), although not without some disagreements in ion modeling. In four examples (PDB:7A4M, 7RRP, 7A6A, 8J5A) a common coordination site near glutamate 27 and 62 is modeled as either sodium (7A6A, 8J5A) or zinc (7A4M, 7RRP) (Fig. 3j). Interestingly in 2 of these cases (8J5A, 7A4M) MIC suggests a 90% or greater probability of zinc. In 7RRP, where this site is modeled as zinc, MIC predicts a 73.4% chance of magnesium. The ion in 7A6A is similarly predicted to be magnesium (42.7%), followed by zinc at 22.1%. Although the generally short coordination distances (1.9–2.1 Å) of two glutamates and a histidine support the choice of zinc in 7A4M and 8J5A (and the choice of either zinc or magnesium for 7A6A, which has a slightly longer ion-histidine distance), the slight outward rotation and imidazole flip of histidine 65 in 7RRP weakens the case for zinc substantially as this interaction is abolished (it should be noted that in the case of 7A4M there is an alternative conformation for histidine 65 that matches 7RRP, however MIC only considers the first alternate conformation for a residue). It is worth noting that different experimental conditions leveraged by different groups may have resulted in different bound cations (consistent with differences in sidechain rotamers/positions between the structures). 7RRP also includes several other ions not found in the other structures, including a zinc interacting with arginine 22 that, given the mismatched charges, should likely be a water or chloride and is predicted by MIC as water with 91.9% confidence (Fig. 3k). A sodium ion is also modeled interacting with the same arginine in 7RRP (Fig. 3k), which is similarly predicted by MIC to be a water with 98.7% confidence. These structures also have numerous waters modeled, and at this high resolution, it is even possible at some sites to observe the slight deformation of the spherical densities due to the water hydrogens, providing experimental evidence for the water in some cases. Examining the 110 water molecules modeled in 7A4M, 106 (96.4%) are predicted to be water by MIC with an average confidence of 91.5 ± 12.5%. Two sites are labeled as chloride at modest confidence (52.9% Cl, 45.8% water for A:HOH:397 and 63.6% Cl, 35.4% water for A:HOH:391, Supplementary Data 4), which is possible given their interactions, but there is not enough evidence for the swap. The other two discrepant sites are immediately adjacent to the zinc site, and are also assigned to be cations (sodium and magnesium) at low confidence (39.7–54.1%). This is a consistent pathology we have observed with MIC for proteins, which is that water molecules that are part of the coordination sphere of a cation are often annotated as cations with low confidence (Supplementary Fig. 2i). This likely stems from the fact that the model is blinded to the identity of the other nearby sites, and waters that are part of a cation coordination shell often have relatively short distances to several anionic side chains and potential ion sites themselves. To account for this, MIC warns when a site is part of a dense cluster of other sites to examine the central, high-confidence site as the probable ion. Overall, the MIC method performs well for the cryo-EM structures, especially those obtained at very high resolution.

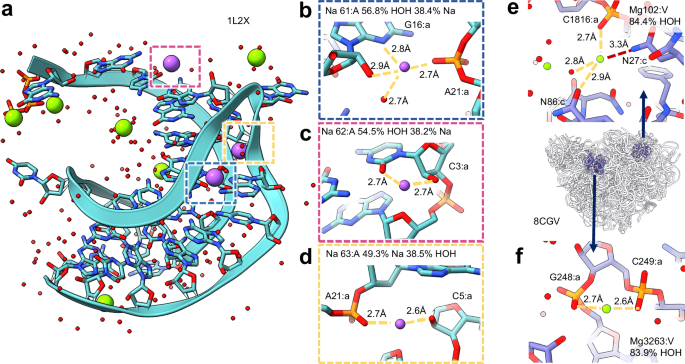

RNA/Ribosomal structure evaluation

We wanted to examine the performance of MIC on structures of RNA, where ion binding is also pivotal2, but only 72 of the 10,364 individual structures in the prevalent ion training set contained RNA or RNA/protein complexes, corresponding to 122 ion/water sites. In general, MIC was still able to perform reasonably well on RNA-bound ions in simple high-resolution RNA structures, likely correctly predicting 9/9 ions in 8D2B, 2/2 ions in 5HNJ, and 6/6 magnesium in 1L2X (Table 1). This includes probable corrections in some cases, for example, predicting the three sodium ions in 1L2X to have a strong potential to be water (Fig. 4a–d). This result is consistent with the overall long coordination distances for a sodium (generally 2.7-2.8 Å vs 2.4 Å expected) and the lack of more than 2 definitive hydrogen bond acceptors or 4 interaction partners total. However, where the model has more difficulties in RNA-bound structures are water molecules, which tend to be overpredicted as cations. For 1L2X, MIC had 76.3% accuracy over the 160 waters with 82.8 ± 14.9% confidence for correct assignments and 64.5 ± 19.6% confidence for incorrect, demonstrating both less accurate and less confident guesses, with every misassignment either sodium or magnesium. Indeed, even the sodium ions in 1L2X likely correctly predicted to be water only have ~ 60% average confidence

a Structure of viral RNA pseudoknot (PDB: 1L2X) with three highlighted sodium sites (navy, magenta, yellow). b–d Sodium sites with either low-confidence water(b, c) or low-confidence sodium (d) MIC predictions. e, f Potentially mismodeled magnesium ions in PDB 8CGV, predicted to be water with high confidence. e MG:V:102. f MG:A:3263.

This trend persists when evaluating MIC on ribosomal structures. In the case of 8CGV, the bacterial 50S ribosome at 1.66 Å resolution, MIC correctly predicts 214/219 magnesium with an average of 95.7 ± 8.6% confidence (although some, such as MG:V:102 and MG:A:3263 which are predicted to be water, are likely mismodeled, Fig. 4e, f), the sole zinc correctly with 100.0% confidence, but only 4865/6570 (74.05%) water molecules with an average confidence of 78.9 ± 16.0% (Supplementary Data 5). Notably, ion accuracy prediction for ribosomal structures showed a significant decrease in accuracy at lower resolutions. We anticipate these results are likely due to the relative paucity of training data (only 56 waters in the training set are from RNA-containing structures) and will improve with further model training on additional deposited structures.

Extended set model training, performance, and manual review

Another potential pitfall highlighted in the RNA work is the lack of inclusion of potassium or other less well-represented ions in the PDB that nevertheless can be found in structures, as the prevalent ion model is incapable of producing the correct answer in these cases. We trained another model that includes potassium, iron, manganese, bromide, and iodide in addition to the prevalent ions and null class (sites with no proximal protein atoms), although there were less than 1000 examples of each of these new classes (Supplementary Figs. 1b, 4a, b). This extended set model achieves an initial accuracy of 79.1% against the deposited test labels and displays similar results to the prevalent ion model in embedding space organization and accuracy by class. The embeddings are again organized primarily by charge as visualized by the UMAP and confirmed by PCA, transitioning smoothly from the halides to water, to monocations, and ending with the transition metals (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 5f–h). Mis-predictions on the test set were often chemically reasonable, such as predicting bromide as either chloride or iodide, iron as zinc, or manganese as magnesium (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Among the added classes, iodide shows a relatively high area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC)72 and precision-recall curve (AUPRC)73 as well as separation between the confidence values of agreeing and disagreeing predictions, indicating successful differentiation of these sites by the extended set model (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e, j, k).

a, b UMAP visualization of training (a) and test (b) set embeddings from trained MIC model with extended site classes: water (blue), zinc (pink), magnesium (teal-grey), sodium (magenta), calcium (yellow), chlorine (green), potassium (purple), manganese (light pink), iron (light purple), bromine (light blue), and iodine (orange). c Confusion matrix of MIC predictions vs revised label following manual review. d Violin plots of the confidence of correct (blue) vs incorrect (pink) MIC test set predictions by class. e Probable mismodeling of a potassium site in PDB 2XEX, predicted as water by MIC with 91.7% confidence.

Similar to the prevalent set, we manually reviewed the set of discrepant ions in the extended test set using the protocol described above (Supplementary Data 6 and Supplementary Fig. 5). This included 251 examples that were predicted to belong to a class different from the deposited label by both the prevalent and extended models as well as an additional 116 disagreeing sites belonging to the added extended classes. We observed a number of similar trends, such as a large number of sodium sites and 12 of the 86 potassium sites corrected to water in our dataset, suggesting that potassium may also be misannotated throughout the PDB (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 5b). The final accuracy of the extended set model following manual review was 86.5%, and confidence was once again a strong measure of correctness for many classes in the prevalent set (zinc, magnesium, water, calcium) and newly introduced classes (potassium, iodide, iron, and bromine) (Fig. 5c, d). We observe worse chloride performance compared to the prevalent-only model, likely from the inclusion of additional halide classes that remain difficult to differentiate due to the low number of training examples. Despite this overall slight decrease in accuracy from the prevalent-only model, it is still able to successfully classify sites belonging to many different ions and can be used when one of these additional ion classes is likely present.

Comparison with existing methods

A number of tools have been developed to perform similar aspects of the process of identifying map features in biomolecular structures15,17,74. However, all of these are limited in some aspect of their scope compared to MIC, for example by only working with structures derived from x-ray crystallography via requiring scattering data, only covering a small subset of possible spherical map features (e.g., only cations), and/or broadly grouping several possible species into one class (e.g., ‘sodium or magnesium’ being considered one class). We have summarized how the applicability of various methods in this space compares to MIC in Supplementary Table 4. Given this, a proper quantitative comparison with many of these methods is challenging, as MIC attempts to provide a precise guess of a specific species for a spherical map feature with an associated confidence across a broad range of different options. For this reason, we chose to focus on comparing our method with the three most similar tools in goal and output: CheckMyMetal, CheckMyBlob, and UnDowser.

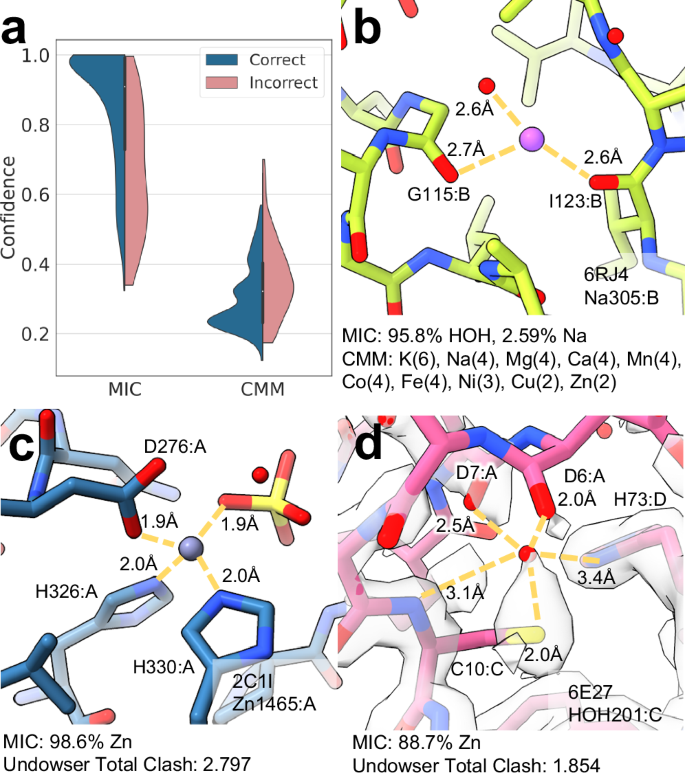

The CheckMyMetal (CMM) web server13,14,15,16 is one of the commonly used structure-based methods to assign identities to cation sites. CMM uses a combination of known binding site properties to evaluate each input structure. Each property (atomic contacts, valence, and geometry) contributes a score between 0 and 2, resulting in a maximum score of 6 for a given ion identity at a particular site. The score of each potential metal is reported, often leading to multiple ions receiving identical and/or comparably high scores. For a fair bulk performance quantitative comparison, we looked only at the subset of test examples that could be identified by both tools: sodium, calcium, magnesium, and zinc. Of these overlapping use cases, MIC assigns the highest confidence to the correct ion identity in 88.3% of cases, compared to 67.0% of CMM predictions. Moreover, 76.3% of these correct CMM predictions have at least one other ion that is tied for the highest score. To further enable direct comparison, we apply a softmax function to the CMM scores to yield a confidence metric analogous to MIC confidence. The resulting CMM confidence is actually lower for correct predictions (0.302 ± 0.09) than for incorrect predictions (0.359 ± 0.11), i.e., CMM is more likely to assign other ions equally high scores when the correct ion has the highest score than when an incorrect ion has the highest score. This analysis demonstrates that CMM is not optimized for large-scale automated prediction of precise identities, as each of these examples must be further inspected to determine final ion assignments. In comparison, MIC’s correct confidence values for this subset are again significantly higher than that of incorrect assignments (0.860 ± 0.167 and 0.665 ± 0.182, respectively), facilitating rapid assignment and highlighting fewer sites that require additional review (Fig. 6a). CMM and MIC have distinct output classes that make each more suitable for specific cases. For example MIC likely identifies the correct label of the deposited sodium ion in 6RJ4 as water with high-confidence (98.5%), while CMM, which does not include water, gives this site a potassium score of 6, followed by a sodium score of 4; re-refinement with water at this position improves both the difference map and interactions at this site (Fig. 6b). CMM does predict the score for several rare metals that are not in the MIC class set due to the sparse deposited examples, including copper, cobalt, and nickel, while MIC includes an explicit prediction for water and halides.

a Confidence of correct (blue) and incorrect (pink) ion assignments by MIC and CMM. b Example of a site (6RJ4:A:Na:305) MIC likely predicts correctly as water (95.8% confidence) over CMM, which assigns a score of 6 for potassium and 4 for six other metals. c Zinc coordination site (2C1I:A:Zn:1465) identified by both MIC and UnDowser with high confidence (MIC zinc confidence: 98.6%, UnDowser clash score: 2.797). d Example of UnDowser and MIC results at a questionably modeled site (6E27:C:HOH:201). This site likely does not contain either an ion or a water, but is predicted to be an ion by both UnDowser (Clash score: 1.854) and MIC (zinc confidence: 88.7%).

Aside from CheckMyMetal, CheckMyBlob (CMB) is another tool with some overlap in use for x-ray crystallography structures. CheckMyBlob uses a classifier trained on numerical features of densities in x-ray crystallography electron density maps to determine ligand identity. The available classes include a number of ions that are identified by MIC, such as water, calcium, and magnesium, with some critical differences; for example, the CMB category of MG-like includes both magnesium and sodium ions, while MIC classifies these separately. To quantitatively compare the two methods, we examined the performance of both methods on two sets: the CMB holdout set entries belonging to these individual categories and a random 25% of the MIC test set for sodium, magnesium, calcium, and zinc (including sites that were corrected to be labeled as Cl or HOH). For the 12,256 CMB holdout examples belonging to the prevalent-only MIC classes (following the removal of 36 examples that overlapped with the MIC training or validation sets), CMB achieves an overall classification accuracy of 66.6%, compared to 68.1% for MIC (Supplementary Data 7). Both tools displayed statistically significant separation by confidence for correct and incorrectly predicted examples (MIC: 0.816 ± 0.17/0.654 ± 0.169, CMB: 0.812 ± 0.20/0.623 ± 0.23), though the effect size for MIC confidence was slightly larger (1.1 vs. 0.87, Supplementary Table 3). For the random ~ 25% of the MIC validation set that CMB was run on, MIC obtained 87.1% accuracy compared to 63.2% for CMB (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). One of the most substantial differences between the two methods for validating sites in structures is that CMB frequently failed to identify sites, particularly sodium (likely due to the relatively subtle map feature compared to other ions), and the CMB web server does not intrinsically validate modeled waters. Despite combining sodium and magnesium into one class, CMB only classifies these entries accurately in 40.2% of observed CMB holdout cases and 54% of our MIC 25% test set cases (Supplementary Fig. 6a, c). MIC successfully distinguishes magnesium from all other classes, including sodium, with 86.7% and 72.9% of Mg sites in the MIC test set and CMB holdout set classified correctly, respectively. (Supplementary Fig. 6b, d). Sodium does remain difficult as discussed above; it should be noted that MIC sodium predictions are sensitive to small mismodeling errors (Supplementary Fig. 2k) and the vast majority of sodium examples (1625/1677, 96.9%) in the CMB holdout dataset have resolutions above the MIC cutoff of 2.0 Å (this difference in the resolution likely contributes substantially to the different performances of the methods on the two datasets, given that 67.7% of examples in the CMB holdout set exceed even 2.5 Å, where resolving ions/water becomes challenging). Further, the CMB ion identities were not subject to manual review. Indeed, in the MIC 25% test set (which is subjected to review) MIC was able to achieve higher accuracy for sodium (69%) than CMB for the joint Na/Mg class (54%; even omitting the ‘null’ sites from CMB produces ~ 76% accuracy for the joint class, approximately equal to the MIC accuracy on both sodium and magnesium individually for this dataset). Finally, CheckMyBlob is only available for x-ray crystallography and cannot be used with cryo-EM structures, limiting its application.

Another tool with some overlapping use is UnDowser, which is intended to find waters that clash with nearby atoms, as these could indicate that the site would better be modeled as a metal. We ran MIC and UnDowser on a randomly selected set of identity-blinded waters and ions to compare the results (see Methods, Supplementary Data 8). UnDowser often agrees with MIC predictions in flagging sites that are likely to belong to a category other than water. Both tools identify the zinc sites in 2C1I (A:1465,1466) with a MIC zinc confidence of 99.9% and 91.4%, and an UnDowser cumulative clash severity score of 2.797 and 2.121, respectively, each comprising of multiple > 0.5 Å polar clashes strongly indicating the presence of an ion (Fig. 6c). Similarly, the magnesium ion in 4RKQ is caught by both tools (MIC: 98.6%, UnDowser: 2.098). Even when MIC is unable to predict the correct identity, it is often able to distinguish what should be an ion binding site, such as the iron sites in 1YFU, predicted as zinc by the MIC prevalent-only model with 97.5% confidence and an UnDowser clash severity score of 1.985. MIC does show a tendency to over-predict ions compared to UnDowser, though similar to the RNA/ribosomal predictions, these assignments typically have a lower confidence (60.6 ± 16.9%) than water predictions that agree with UnDowser (90.1 ± 11.5%), helping the user handle these cases. UnDowser and MIC both fail where the modeling is questionable, as is the case for 6E27:C:HOH:201, which both MIC and UnDowser flag with high zinc confidence and clash score (92.5%, 1.854 Å). However, 6E27 shows no major positive difference density and lacks density in the 2Fo-Fc map for much of the protein at this site (Fig. 6d). UnDowser provides information about the charge of clashing atoms that can assist the user in interpreting the results, but does not explicitly attempt to predict the true ion identity. UnDowser does not calculate any clashes for halides such as the chlorines in 3MUJ and 4RKQ, which are predicted correctly by MIC. Ultimately, these are complementary but not overlapping methods of confirming correct modeling, and users should choose the tool that best aligns with their specific requirements.

Alternative models

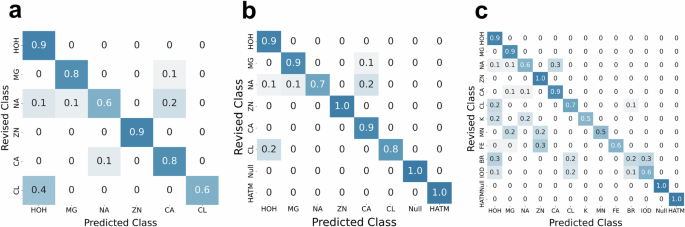

In addition to the standard models presented above, alternative versions of MIC were trained for specific use cases. We have implemented the prevalent model as MIC-ChimeraX (MIC-CX), a plugin for the UCSF ChimeraX molecular visualization program. This tool automatically generates the fingerprints of all ions and waters in the provided structure, or on the subset of the currently selected set of waters and ions. A separate prevalent ion model trained on these ChimeraX-specific fingerprints is used to generate predicted probabilities for each input. The results are automatically visualized and available for export. MIC-CX achieves an accuracy of 84.5% on the prevalent test set (following manual correction of misannotated examples) (Fig. 7a). MIC-CX is installable through the built-in Toolshed. It is important to note that MIC fingerprints cannot be used with MIC-CX due to slight differences in the LUNA vs. ChimeraX atomic invariants and chemical group protocols (see “Methods”).

a Performance of the prevalent class MIC-ChimeraX model. b MIC-HATM-C prevalent model performance. c MIC-HATM-C extended model performance.

Furthermore, we also include the MIC-HATM-C carbon model that adds a category for cases in which small molecule ligand atoms might result in spherical densities that resemble ions or waters (e.g., due to flexible carbon chains). These fingerprints are calculated by using the center of a non-aromatic carbon in a small molecule ligand (see Methods for additional detail). The prevalent and extended models trained on this dataset achieve an accuracy of 91.2% and 85.9% on the corrected test set, respectively (Fig. 7b, c). We hope that these additional models will be useful in these specific cases as well as increase the accessibility of the tool for the community.