author:

(1) Sasun Hambarzumian, Active Loop, Mountain View, California, USA

(2) Abhinav Tuli, Active Loop, Mountain View, California, USA

(3) Levon Ghukasian, ActiveLoop, Mountain View, California, USA

(4) Fariz Rahman, Active Loop, Mountain View, CA, USA.

(5) Hrant Topchyan, Activeloop, Mountain View, California, USA

(6) David Isayan, Active Loop, Mountain View, CA, USA

(7) Mark McQuaid, Active Loop, Mountain View, CA, USA

(8) Mikhail Harutyunyan, Active Loop, Mountain View, California, USA

(9) Tatevik Hakobyan, Activeloop, Mountain View, California, USA

(10) Ivo Stranik, Active Loop, Mountain View, California, USA

(11) David Buniatian, Active Loop, Mountain View, CA, USA.

List of Links

4. Overview of the Deep Lake System

As shown in Figure 1, Deep Lake stores raw data and views in object storage such as S3, materializing datasets with complete lineage. The streaming, Tensor Query Language queries, and visualization engines run on the deep learning compute or browser without the need for external management or centralized services.

4.1 Ingestion

4.1.1 Extract. In some cases, your metadata already resides in a relational database. Additionally, we've built an ETL destination connector with Airbyte.[3] [22]The framework allows you to connect to any supported data source, including SQL/NoSQL databases, data lakes, and data warehouses, and sync the data into Deep Lake. The connector protocol transforms the data into a columnar format.

4.1.2 Conversion. To significantly speed up the data processing workflow and free users from having to worry about chunk layout, Deep Lake provides the option to run Python transformations in parallel. A transformation takes in a dataset, iterates over the first dimension sample by sample, and outputs a new dataset. The user-defined Python function requires two mandatory arguments 𝑠𝑎𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑒_𝑖𝑛, 𝑠𝑎𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑒_𝑜𝑢𝑡, and is decorated with @𝑑𝑒𝑒𝑝𝑙𝑎𝑘𝑒.𝑐𝑜𝑚𝑝𝑢𝑡𝑒. Multiple datasets can be dynamically created for a single dataset, allowing both one-to-one and one-to-many transformations. Transformations can also be applied on the fly without creating a new dataset.

Behind the scenes, the scheduler batches sample-by-sample transforms that work on nearby chunks and schedules them to a process pool, optionally delegating the computation to a Ray cluster. [53]Instead of defining an input dataset, users can provide arbitrary iterators, including custom objects, to create an ingestion workflow. Users can also stack multiple transformations to define complex pipelines.

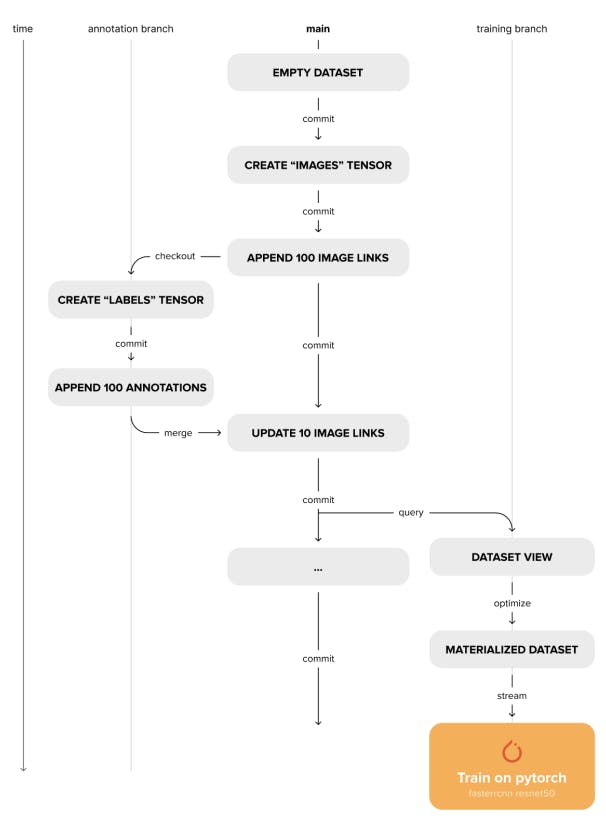

4.2 Version Control

Deep Lake also addresses the need for reproducible experiments and adherence to full data lineage. Different versions of a dataset reside in the same storage, separated by subdirectories. Each subdirectory acts as an independent dataset with a metadata file. Unlike unversioned datasets, these subdirectories contain only the chunks that were modified in a given version and a corresponding chunk_set per tensor that contains the names of all modified chunks. A versioning information file at the root of the directory tracks the relationship between these versions as a branching versioning tree. When accessing a chunk of a tensor in a given version, the versioning tree is traversed starting from the current commit toward the initial commit. During the traversal, the chunk set of each version is checked for the presence of the required chunk. If the chunk is found, the traversal is stopped and the data is retrieved. To track differences between versions, each version also stores a commit diff file for each tensor. This allows for fast comparisons between versions and branches. In addition, IDs for samples are generated and stored during dataset creation, which is important for tracking the same samples during merge operations. Deep Lake's versioning interface is a Python API that allows machine learning engineers to manage dataset versions within their data processing scripts without having to switch between CLIs. The following commands are supported:

• Dedication: Creates an immutable snapshot of the current state of the dataset.

• check out: checkout to an existing branch/commit, or create a new branch if it doesn't exist.

• Diff: Compare the differences between two versions of a dataset.

• merge: Merge two different versions of a dataset and resolve conflicts according to user-defined policies.

4.3 Tensor Visualization

Data visualization is a critical part of ML workflows, especially when data is difficult to analyze analytically. Fast, seamless visualization can speed up data collection, annotation, quality inspection, and training iterations. Deep Lake Visualizer Engine provides a web interface for visualizing large-scale data directly from the source. It considers the htype of tensors to determine the best layout for visualization. Primary tensors such as image, video, audio are displayed first, and secondary data and annotations such as text, class_label, bbox, binary_mask are overlaid. Visualizer also considers meta type information such as sequence to provide a sequential view of the data. This allows you to play a sequence or jump to a specific position in a sequence without retrieving the entire data. This is relevant for video and audio use cases. Visualizer addresses a critical need in ML workflows, enabling users to understand and troubleshoot data, depict the evolution of data, compare predictions to ground truth, and view multiple image sequences (e.g. camera images and disparity maps) side by side.

4.4 Tensor Query Language

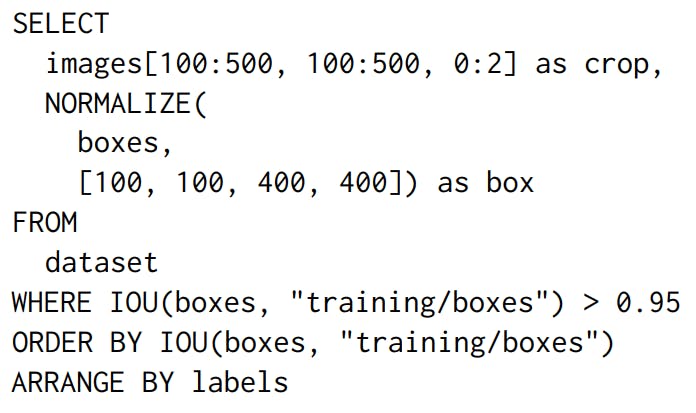

Querying and balancing datasets is a common step in training deep learning workflows. Typically, this is achieved within the data loader using sampling strategies or separate pre-processing steps to sub-select the dataset, whereas traditional data lakes connect to external analytical query engines. [66] It streams DataFrames into your data science workflow. To solve the gap between formatting and fast access to specific data, it provides a built-in SQL-like query engine implemented in C++ called Tensor Query Language (TQL). Example queries are shown in Figure 5. The SQL parser is extended from Hyrise, [37] To design the Tensor Query Language, we implemented a planner and an execution engine that can optionally delegate computation to external tensor computation frameworks. The query plan generates a computation graph of tensor operations. A scheduler then executes the query graph.

Query execution can be delegated to external tensor computation frameworks such as PyTorch. [58] or XLA [64] It efficiently leverages the underlying accelerated hardware. In addition to standard SQL capabilities, TQL also implements numerical computations. There are two main reasons for implementing a new query language. First, traditional SQL does not support multidimensional array operations, such as calculating the average of image pixels or projecting an array to a specific dimension. TQL solves this problem by providing a number of convenience functions for adding Python/NumPy style indexing, slicing arrays, and manipulating arrays. Many of these functions are common operations supported by NumPy. Second, TQL allows queries to be more deeply integrated with other Deep Lake features such as versioning, streaming engine, and visualization. For example, TQL allows you to query data for a specific version or across multiple versions of a dataset. TQL also supports specific instructions for customizing visualization of query results, as well as seamless integration with data loaders for filtered streaming. The built-in query engine runs alongside the client while training models on remote compute instances or within the browser compiled with WebAssembly. TQL extends SQL by performing numerical calculations on multidimensional columns. It allows you to build views of a dataset and then visualize it or stream it directly to deep learning frameworks. However, the query views can be sparse, which can impact streaming performance.

4.5 Reification

Most of the raw data used for deep learning is stored as raw files (compressed in formats such as JPEG) locally or on the cloud. A common way to build a dataset is to store pointers to these raw files in a database, query it to get the subset of data you need, fetch the filtered files to your machine, and then iterate over the files to train your model. Furthermore, data lineage must be maintained manually using provenance files. Tensor Storage Format simplifies these steps by using linked tensors, which store pointers to the original data (links/URLs to one or more cloud providers). Pointers in a single tensor can connect to multiple storage providers, allowing users to get a unified view of data residing in multiple sources. All the features of Deep Lake, including querying, versioning, and streaming to deep learning frameworks, are available with linked tensors. However, data streaming performance is not as optimal as with default tensors. Sparse views created by queries suffer from similar issues, but stream inefficiently due to the chunk layout. Furthermore, materialization transforms the dataset view into an optimal layout and streams it to the deep learning framework for faster iteration. Materialization involves taking the actual data from links or views and efficiently laying it out in chunks. Performing this step at the end of the machine learning workflow minimizes data duplication, ensuring optimal streaming performance and minimal data duplication, and complete data lineage.

4.6 Streaming Data Loader

As datasets grow larger, storing and transferring them over the network from remotely distributed storage becomes unavoidable. Data streaming allows training models without waiting for all data to be copied to the local machine. The streaming data loader reliably retrieves data, decompresses it, applies transformations, collates it, and hands it over to the training model. Deep learning data loaders typically delegate retrieval and transformations to parallel running processes to avoid synchronous computation. The data is then transferred to the main worker via inter-process communication (IPC), which incurs memory copy overhead or uses shared memory with reliability issues. In contrast, the Deep Lake data loader delegates highly parallelized retrieval and in-place decompression in C++ per process to avoid the Global Interpreter Lock. It then passes the in-memory pointer to a user-defined transformation function for collation before exposing it to the training loop in the Deep Learning native memory layout. When using only native library routine calls, the transformations are executed concurrently in parallel, releasing the Python Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) accordingly. As a result, we have the following:

• performance: Deliver data to deep learning models fast enough that the GPU is either fully utilized or bottlenecked by computation.

• Smart SchedulerDynamically differentiates between the priorities of CPU-intensive and less intensive jobs.

• Efficient resource allocation: Estimate memory consumption to avoid interrupting the training process due to memory overfilling.

[3] The source code is available at https://github.com/activeloopai/airbyte in the branch @feature/connector/deeplake.