Material

The dataset was part of the Cognitive Resilience and Sleep History research project. Fifty-seven participants volunteered in the research experiment at the University of California, Santa Barbara. No demographic data was provided. The Human Participants Committee of the University of California Santa Barbara (#IRB00000307) and the Army Research Laboratory Human Research Protections Office approved all study procedures. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations. All participants provided written informed consent.

Each participant followed a standardized protocol, beginning with a relaxation period of 6 min (referred to as “REST”), followed by the completion of four distinct cognitive tasks. Participants could return for up to 10 sessions on separate days (median = 6, SD = 3.33).

Four cognitive tasks were widely recognized cognitive assessments; they were designed to probe various aspects of mental functioning. A brief overview of each task was described below:

Dot Probe Task (DPT): This task involved the display of two facial images, each categorized by emotion (angry, happy, or neutral). A subsequent visual probe would appear, and participants asked to identify the probe’s location (left or right). The DPT measured how much faster participants responded to angry stimuli compared to neutral stimuli. DPT is a classic assessment of selective attention (160 trials per session).

Mental Arithmetic (MA): Participants solved modular arithmetic problems, with varied in difficulty level (easy and hard). MA tasks were considered a core component of human logical thinking and related to attention, working memory, processing speed, MA ability, and executive function. The difficulty level was presented randomly (40 trials per session).

Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT): Participants pressed a key when a visual stimulus appeared on the screen. The PVT was a classic measure of sustained attention that measures how participants respond to a simple visual stimulus for an extended period of time (77 trials per session).

Visual Working Memory (VWM): Participants memorized a stimulus image and compared it to a second image. The second image could be similar or different. Participants were asked to determine whether the second image matched the first, with difficulty levels varying (1 item for easy level to 6 items for hard level). Each session had 48 trials.

Data was recorded at 250 Hz, capturing pupil diameter, gaze position (Gaze X, Gaze Y). Additionally, behavior data were collected, including the initiation time of each trial (Stimulus Time, ST), and task-specific information. In this paper, ST was used as a primary predictor of cognitive events.

Sampling method

The goal was to auto-detect cognitive events. ST signified the beginning of each trial, marking new information for participants to process. Therefore, each ST was a cognitive event, and we wanted to predict the location of the ST. The input data had 1-s intervals of three time-series features (Pupil Diameter, Gaze X, and Gaze Y), each recorded at a sampling rate of 250 Hz. The problem was framed as a binary classification task, where the model’s output yielded a probability ranging from 0 (absence of ST) to 1 (presence of ST).

To account for individual differences, we standardized the dataset per participant and session. Participants had different pupil diameters and reacted differently toward ST and PLR. For participants with multiple repeated sessions, we treated each session as a separate entity due to differences in pupil diameter between sessions. These differences may have resulted from factors such as variations in equipment calibration, lighting conditions, or participants’ mental states. To address this, standardization involved calculating the mean and standard deviation of each session, scaling the data to set the mean of data at 0, and the standard deviation at 1. This approach helped minimize the individual variations.

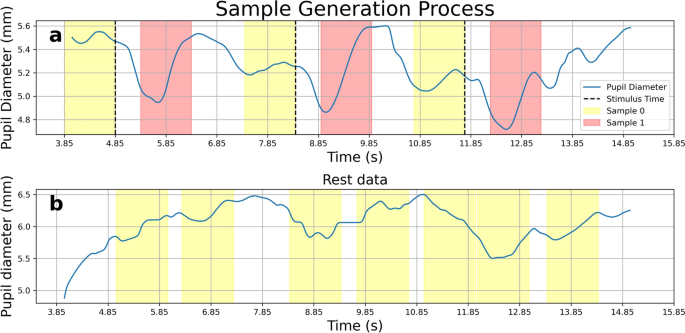

Let the time of ST was at 0 s, for each ST, two samples were generated: sample labeled “0” (absence of ST) from − 1 to 0 s and one sample labeled “1” (presence of ST) from 0.5 to 1.5 s. We chose the start time of 0.5 s to minimize the influence of the PLR that may occur with stimulus presentation16,46. Typically, the initial constriction phase of the pupil took about 0.9 to 1-s33,49. However, in our dataset, we found that the pupil reached its minimum diameter in approximately 0.6–0.7 s. Since our goal was to capture cognitive responses, we chose to avoid the majority of the constriction phase. In addition, as discussed in “Exploratory data analysis” section, the 0 to 0.5-s window corresponded to saccadic eye movements, during which participants shifted their focus to newly presented information. The pupil dilation occurred after 0.5 s when participants began processing the stimulus. Therefore, we determined that a time frame of 0.5–1.5 s was appropriate to predict cognitive events.

Next, we randomly selected a 1-s window from “REST” data, and labeled it as a “0” sample. All “REST” data samples were non-overlapping. The process for sample generation was illustrated Fig. 5.

Sample generation process. The panel (a) displayed on task data. The black dotted line was the Stimulus Time (ST). For every ST, the generation process generated one “0” sample (yellow) and one “1” sample (red). The panel (b) displayed REST data, where non-overlapping “0” samples were randomly generated. Each sample contained 1 s of data.

Following data sampling, any missing data samples were removed. Missing data was caused when the eye-tracking devices failed to capture participants’ pupil signals, either because participants looked away from the screen or due to technical errors. After removing invalid samples, the dataset exhibited an imbalance, with “0” class samples being the majority. The percentage for the “1” class was 40%, 34%, 23%, 28%, and 40% for All-task, DPT, MA, PVT, and VWM, receptively. We applied SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) to rebalance only the training dataset, while the testing dataset remained unchanged. After SMOTE, the class distribution in the training set was 1:1. This helped the models avoid statistical bias toward either class.

Then, we split the fifty-seven participants into five folds. Two folds had 12 participants each and three folds had 11 participants each. Unlike the standardization process, the splits were made at the participant level rather than at the session level or sample level to avoid data leakage. Splitting by samples could allow samples from the same participant to appear in both the training and testing set, causing data leakage and artificially inflating model performance. After splitting, we applied five-fold cross-validation. In each iteration, three folds were used for training, one fold for validation, and one fold for testing.

Models architecture

All four model architectures shared a common overall structure and used the same loss function. The distinctions were laid in their specific layer. The layer for each architecture was detailed below, where x denoted the input, b was the bias and y was the output, \(\phi\) was the ReLU activation function and M was a dropout matrix with a dropout rate of 0.3.

CNN: The architecture was a sequential convolutional neural network (CNN). Each layer included a convolutional layer with a ReLU activation function, followed by a max-pooling layer, and a dropout layer. The mathematical representation for each layer was expressed as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} y = M \odot P(\phi (W_{conv} * x + b)) \end{aligned}$$

(1)

where \(W_{conv}\) represented the 1D convolution tensor with a filter size of 5, stride 1, and 64 output channels. P was the max-pooling operation with size 2.

BiLSTM: The architecture was a bidirectional long short-term memory with each layer that could be expressed in mathematical terms as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} y = M \odot [LSTM_f(x);LSTM_b(x)] \end{aligned}$$

(2)

where \(LSTM_f\) and \(LSTM_b\) were forward and backward LSTM layers, each with a hidden dimension of 64.

RNN: The architecture was a simple recurrent neural network (RNN). The hidden state update and final output were given by:

$$\begin{aligned} \{h_t\}_{t=1}^{250} = \{ M \odot (W_x*x_t + W_h*h_{t-1} + b) \}_{t=1}^{250}, \ \ y = h_{250} \end{aligned}$$

(3)

where t was the time-step that was recurrent from 1 to 250. \(x_t\) and \(h_t\) were the input x and the hidden state h at timestep t. h had the dimension of 128. \(W_x\) and \(W_h\) were the weight matrix for the input x and hidden state h, respectively. The output y was equal to \(h_{250}\), the hidden state in timestep 250.

MLP: The architecture was a multilayer perceptron. Each perceptron layer could be expressed in mathematical terms as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} y = M \odot \phi (Wx + b) \end{aligned}$$

(4)

W was the weight matrix with hidden dimension 128.

All four architectures shared the same general structure and produced two outputs: a classification output \({\hat{Y}}_{clf}\) and a pupil diameter output \({\hat{Y}}_{PD}\). The \({\hat{Y}}_{clf}\) generated a probability score ranging between 0 and 1, where 0 value indicated the absence of ST, and 1 value indicated the presence of ST. It was the main output for optimization. The \({\hat{Y}}_{PD}\) output aimed to reconstruct the pupil diameter from the input sample. It was used solely for review and error-checking purposes. The architecture equation was defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} ({\hat{Y}}_{clf}, {\hat{Y}}_{PD}) = W_{l} \cdot P_{ave}(L_4(L_3(L_2(L_1(X)))))) + b_{l} \end{aligned}$$

(5)

where X was the input sample with three dimensions (N, 250, 3), except for the MLP, which received a reshaped size of (N,750). N was the number of samples, the second dimension was the temporal dimension corresponding to 1 s at 250 Hz, and the third dimension was 3 features (Pupil Diameter, Gaze X, and Gaze Y). Since the MLP could not process temporal sequences directly, the temporal and feature dimensions were merged (i.e., \(250 * 3=750)\). The layers \(L_1, L_2, L_4, L_4\) were architecture-specific and differed depending on the model (as described in Eqs. 1–4). The \(P_{ave}\) referred to the average pooling operation applied exclusively to the temporal dimension, without affecting the other dimensions, to reduce the temporal dimension. This averaging pooling was not applicable in the MLP architecture. The \(W_l\) and \(b_l\) were the weight and the bias for the final linear layer. The \({\hat{Y}}_{clf}\) and \({\hat{Y}}_{PD}\) were the output of the architecture.

All models trained using the same composite loss function that combined cross-entropy loss, \({\mathcal {L}}_{cel}\) for the classification output \({\hat{Y}}_{clf}\) and L1 loss \({\mathcal {L}}_{MAE}\) for the pupil diameter output \({\hat{Y}}_{PD}\). The overall loss function could be expressed as:

$$\begin{aligned} {\mathcal {L}} = {\mathcal {L}}_{cel}(\sigma ({\hat{Y}}_{clf}), Y) + \alpha * {\mathcal {L}}_{MAE}(\phi ({\hat{Y}}_{PD}), X_{PD}) \end{aligned}$$

(6)

where \(\sigma\) and \(\phi\) were the Sigmoid and ReLU activation functions respectively. The Y was the ground true classification label (either 0 or 1). \(\alpha = 0.004\) was a constant scalar, and \(X_{PD}\) was the ground true for the input sample containing only the Pupil Diameter feature after removing the Gaze X and Gaze Y features. The \({\hat{Y}}_{PD}\) output was designed for error-checking purposes. If the models were unable to reconstruct the original output from its last layer, it signaled a potential mathematical error within the architecture. However, this should not affect the overall performance of the model. The coefficient \(\alpha\) was selected to be small enough to not affect the classification performance, and non-zero to ensure that the model does not neglect the reconstruction task. After testing, we determined that 0.004 was appropriate for the coefficient \(\alpha\).

We trained five distinct models for each architecture described above. The key distinction between these models was the training data used. Four models were task-specific, namely “DPT”, “PVT”, “MA”, and “VWM”, trained exclusively on data from their respective tasks. In contrast, the “All-task” model was trained on the entire available training dataset, aiming to evaluate the architecture’s ability to generalize across various tasks.

Evaluation metric and feature importance algorithms

We selected the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) as the primary metric. This choice was made because the dataset was imbalanced. MCC was known for its robustness in handling imbalanced datasets50,51. Alongside MCC, we included several secondary metrics such as accuracy, F1 score, sensitivity, and specificity.

For the third objective mentioned in the “Introduction” section, we aimed to understand the factors influencing our model’s predictions by performing a feature importance analysis. This analysis helped identify which feature contributed the most weight to the output. We used the Permutation Feature Importance algorithm52 to compute feature importance.

Initially, we established a baseline score, denoted \(s_{base}\). We evaluated testing samples without any alterations. \(s_{base}\) was measured in terms of MCC. Then, we assessed the score for each feature. To accomplish this, we randomly shuffled all data within a specific feature, keeping all other features unchanged. This process allowed us to isolate the impact of the feature under examination. Following this, we conducted predictions and computed the score for these perturbed samples \(s_{i}\) anticipating a decrease in performance compared to \(s_{base}\). The decrease in performance was quantified and subtracted from \(s_{base}\). This iterative process was repeated for all features. To ensure the reliability of these feature importance metrics, we repeated these experiments 100 times \((N = 100)\) and calculated the mean and standard deviation across all features, as expressed in Eq. (7):

$$\begin{aligned} I_{j} = \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N}{(s_{base} – s_{i,j})} \end{aligned}$$

(7)

where, \(I_{j}\) represented the importance score for feature j, and \(s_{i,j}\) was the MCC score for feature j in the i-th iteration.