The starting dataset

This section provides information about the dataset used for the analysis, consisting of radon and meteorological time series.

Radon monitoring stations

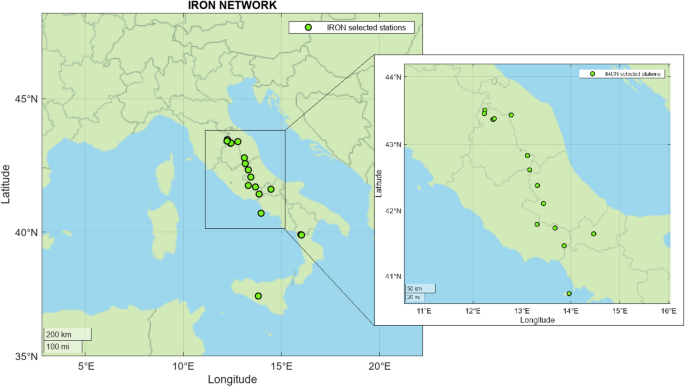

Locations of the IRON stations used in this study (green dots), distributed across central and southern Italy (refer to Table 6 for latitude/longitude coordinates of each station). The figure has been realized using MATLAB® version 2024a).

Since 2009, the IRON network27 has been providing near real-time measurements of radon emissions from various stations located throughout Italy, mainly concentrated in the Central-Southern Apennines (see Fig. 5). The stations included in this study differ in both their installation types and the radon detectors employed. Specifically, radon has been measured passively using proprietary INGV instruments based on Lucas cell detectors, from here named just Lucas, and AER-C Algade©(http://www.algade.com/) detectors. For Lucas, radon gas diffuses into the detector’s flask, whose inner wall is coated with silver-activated zinc sulfide (ZnS), serving as the scintillating material that detects radon progeny. Lucas configured acquisition window is about 2 hours long (115 minutes of data acquisition followed by 5 minutes of standby time). The minimum detectable concentration ranges from 3 to \(6\;\text {Bq}/\text {m}^3\), depending on the electronics used and variations in the deposition of the ZnS scintillating layer within the Lucas cell. AER-C is a small sized commercial solid-state radon detector. The sensitivity of this instrument ranges between 15 and \(20\;\text {Bq}/\text {m}^3\) per pulse per hour. The acquisition window has been configured to 4 hours and measurements have been adjusted for local absolute humidity28.

As detailed in Table 6, the majority of detectors’ installations are indoor (\(44\%\)) and shelter (\(33\%\)). Indoor detectors are located in the basement of a building, typically in a room with the smallest aeration system possible and with restricted access, in order to reduce the influence of any anthropogenic activities. In the case of shelter installation, the radon instrument is housed in a small shelter alongside other seismic and/or geodetic monitoring equipment. In borehole (\(17\%\)) and cavity (\(6\%\)) installations, the radon detector is placed in boreholes less than 2 meters deep and in underground cavities, such as aqueducts, tunnels or mines, respectively.

Starting from the available IRON dataset29,30, this study focuses on radon data corrected for internal humidity dependency. Among these, radon time series with corresponding meteorological data were retrieved from a PostgreSQL relational database (specifically designed and implemented to support IRON31,32). Since the installation of different instruments at the same station can generate inconsistent time series, we treated as separate series those defined by different station-instrument pairs. We then selected radon time series spanning at least two and a half years. Finally, we excluded the following ones, from stations

-

RDP, RDPT, RPD1, RDP2: These series are highly discontinuous due to significant human activity and ongoing construction work in the area.

-

MURB: This serie exhibits an excessively high trend toward the end, making it completely unpredictable.

As a result, the final dataset consists of 18 time series: two from the FRME station (denoted as FRME_E146 and FRME_H146) and the remaining from different stations, which are referred to simply only by their station acronyms.

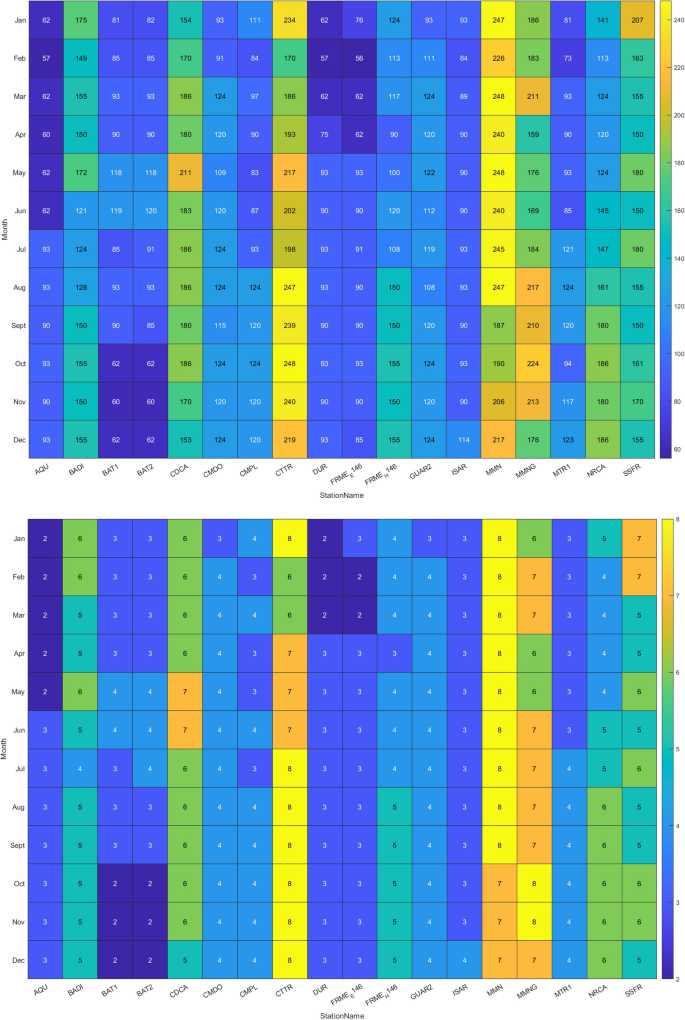

Table 6 provides the start and the end dates for each downloaded radon time series. Some data gaps exist, corresponding to periods when no data were acquired. The last column of Table 6 indicates the number of effective days, excluding the intervals when the radon detector was inactive. Despite the data gaps, the selected time series are sufficiently long to capture the seasonal variations of radon, with all time series providing a sufficient coverage for analyzing radon seasonal trends. Figure 6 highlights the consistency of data collection across the stations, showing the number of days per month in the respective time series.

The radon levels used in this study were smoothed using a 15-day moving average, a procedure previously adopted for managing IRON acquisitions10,11. Each data point was smoothed by a mean calculated over a sliding window of length 15 days across neighboring elements, centered about the current and previous data points.

(Top) Heat map displaying the total number of days per month during which each station collected data throughout its entire deployment period. The intensity of the color indicates the frequency of data collection, with brighter shades representing more measurements. For example, the “CTTR” station shows 248 days of data collection in October over a span of 8 years, indicating that it operated every day of October each year. (Bottom) A heat map similar to the top one, but highlighting the number of times the station recorded at least one measurement in a given month throughout its entire deployment. For example, the “CDCA” station shows the number 6 for July, meaning that over its 7-year deployment, there was at least one data point recorded in July for 6 of those years.

Meteorological stations

Radon measurements have been analyzed together with the time series of the following meteorological variables: temperature (\(^\circ \text {C}\)), pressure (mb), rainfall (mm/h), relative humidity (\(\%\)), solar radiation (\(\text {W/m}^2\)), and wind strength (kn). Temperature was measured along with radon at each IRON station, while other meteorological data were collected from 3B Meteo meteorological stations located near the IRON stations (see Table 7). On average, the meteorological stations are approximately \(5.7\pm 5.7\;\text {km}\) away from the corresponding IRON stations, with the farthest distance being 22 km. Dedicated procedures were developed to automatically retrieve data from the 3B Meteo stations on a daily basis. Weather data were collected hourly, resampled to match the time intervals of the radon measurements, and then smoothed applying a 15-day moving average, as for radon data.

Regression analysis

Regression analysis is a statistical technique used to quantify and model the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. The simplest form of regression is a linear model, where the dependent variable is expressed as a linear combination of the input variables:

$$\begin{aligned} y = \beta _0 + \sum _{i=1}^n \beta _i x_i = \beta _0 + \beta _1 x_1 + … + \beta _n x_n \end{aligned}$$

(1)

In a supervised learning framework, the goal is to estimate the parameters \(\beta _i\) that best describe this relationship, ensuring that the predicted values of y are as close as possible to the observed data. The most common method is least squares estimation, which minimizes the sum of squared residuals across all data points.

In this study, we used two distinct regression approaches to analyze radon time series, focusing specifically on capturing periodic variations on an annual timescale, as it is well known that radon levels exhibit just diurnal and yearly periodicity11. In the first approach, we used the meteorological variables listed in “Meteorological stations” section as predictors. In the second approach, we introduced dummy variables to better account for radon temporal patterns. A temporal dummy variable is a binary categorical variable that segments a time series into distinct seasonal components, allowing the regression model to account for periodic variations of the dependent variable35. We introduced four types of dummy functions: monthly, fortnightly, weekly, and half-weekly. Each function takes the value 1 during its corresponding time period and 0 otherwise. For example, the monthly dummy function for January is set to 1 for all January observations, regardless of the year, and 0 for all other months.

The two approaches just presented result in five distinct regression models:

-

1.

Meteorological model: capturing temporal variations of radon as a response of meteorological condition,

$$\begin{aligned} y_{\text {meteo}} = \beta _0 + \beta _T x_T + \beta _P x_P + \beta _R x_R + \beta _H x_H + \beta _S x_S + \beta _W x_W \end{aligned}$$

(2)

where \(\beta _T\), \(\beta _P\), \(\beta _R\), \(\beta _H\), \(\beta _S\), and \(\beta _W\) represent the regression coefficients associated with temperature \(x_T\), pressure \(x_P\), rainfall \(x_R\), relative humidity \(x_H\), solar radiation \(x_S\), and wind strength \(x_W\) respectively.

-

2.

Monthly model: capturing seasonal variations on a monthly scale,

$$\begin{aligned} y_{\text {month}} = \beta _0 + \sum _{m=1}^{12} \beta _m D_m \end{aligned}$$

(3)

where \(D_m\) represents the dummy variable for month m, which takes the value 1 if the observation belongs to month m and 0 otherwise.

-

3.

Fortnightly model: accounting for biweekly cycles in radon concentrations,

$$\begin{aligned} y_{\text {fortnight}} = \beta _0 + \sum _{f=1}^{26} \beta _f D_f \end{aligned}$$

(4)

where \(D_f\) represents the fortnightly dummy variable, dividing the year into 26 two-week periods.

-

4.

Weekly model: identifying weekly fluctuations in radon levels,

$$\begin{aligned} y_{\text {week}} = \beta _0 + \sum _{w=1}^{52} \beta _w D_w \end{aligned}$$

(5)

where \(D_w\) denotes the weekly dummy variable, which takes the value 1 for observations in week w and 0 otherwise.

-

5.

Half-weekly model: capturing finer temporal variations,

$$\begin{aligned} y_{\text {halfweek}} = \beta _0 + \sum _{h=1}^{104} \beta _h D_h \end{aligned}$$

(6)

where \(D_h\) represents a half-weekly dummy variable, dividing the year into 104 half-week intervals.

These regression models have been applied to each of the 18 of radon time series (Table 6), and results have been compared to assess the effectiveness of dummy variables in reconstructing the average radon trend. Each regression was trained using the first \(80\%\) of the data and tested on the remaining last \(20\%\) to ensure robust evaluation. It is important to highlight that the test periods were specifically chosen to occur at the end of each time series, allowing us to assess the models’ forecasting performance for future, unseen data. Table 8 specifies training and test time intervals for each station. The table also specifies which seasons are covered by the test time interval for at least one month, confirming that the models were tested across different seasonal conditions. The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) was used to assess model performance. MAPE provides a standardized measure of predictive accuracy and is defined as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {MAPE} = \frac{100}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N}\left| \frac{A_{i}-F_{i}}{A_{i}} \right| \end{aligned}$$

(7)

where \(A_{i}\) is the actual value, \(F_{i}\) is the forecast value and N is the total number of points.

Statistical tests

The MAPE values on the test datasets were compared using two different statistical tests: the Smirnov test (known also as two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; KS), and the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

The Smirnov test is a nonparametric statistical test33 that quantifies the difference between two Empirical Cumulative Distribution Functions (ECDFs). In this study, we applied it to compare the ECDF of the MAPE values from the meteorological model with the ECDF of the MAPE values from each dummy model. By measuring the maximum absolute difference between the two ECDFs, the test helps assess whether the error distributions of the dummy models deviate significantly from that of the meteorological model. Mathematically, given two cumulative distribution functions \(F_1(x)\) and \(F_2(x)\), the Smirnov statistics \(D_n\) is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} D_n = max_x |F_1(x) – F_2(x)| \end{aligned}$$

(8)

The null hypothesis \(H_0\) states that the two distributions are identical. The test returns a p-value that determines whether to reject \(H_0\) at a given significance level (0.05 in this case). Since the Smirnov test is sensitive to differences in both the location and shape of distributions, it is useful for detecting deviations in the overall error structure.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a widely used nonparametric procedure34, but instead of comparing full distributions, it assesses a zero-median difference between two sampled populations with paired observations. In the two-tailed version of the test, the null hypothesis \(H_0\) states that the median of the differences between the two paired samples is zero, meaning there is no significant difference in the central tendency between the two distributions. In our study, the Wilcoxon two-tailed test was used to compare the MAPE values of the meteorological model with those of each dummy-based model. If the p-value from the test is below the significance threshold (0.05), it indicates that there is a significant difference between the two models.

For this study, we also applied the one-tailed (right-sided) version of the Wilcoxon test to determine whether the dummy models outperforms the meteorological one, with the null hypothesis \(H_0\) stating that the median of the dummy model errors is more than or equal to the median of the meteorological model errors. A low p-value (below 0.05) would indicate that the meteorological model produces significantly higher errors than the dummy models, whereas a higher p-value would suggest no strong evidence against equivalence.

Each of these tests contributes a different perspective: the Smirnov statistics checks for overall distribution differences, while Wilcoxon one focuses on median differences. Together, they offer a comprehensive statistical evaluation of whether the dummy models can be considered interchangeable with the meteorological model.