Pain related data

The acquisition of pain-related data has been described in detail previously9. Briefly, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Medicine, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany (approval number 150/11). Informed written consent was obtained from each of the participants, who were 125 unrelated healthy Caucasian volunteers (69 men, 56 women, aged 18–46 years, mean 25 ± 4.4 years) in whom pain thresholds to thermal, mechanical, and electrical stimuli were determined in nonsensitized and sensitized skin areas of the forearm in an open, nonrandomized design.

The study assessed pain thresholds defined as “the least experience of pain which a subject can recognize” (http://www.iasp-pain.org) and implemented in the study as the physical strength at which the answer to the question “does it hurt?” changes from “no” to “yes”, which is why the units of pain thresholds are the units of physical strength of the applied stimuli. Thermal stimuli comprised heat and cold. Heat stimuli were applied using a 3 × 3 cm thermode (Thermal Sensory Analyzer, Medoc Advanced Medical Systems Ltd., Ramat Yishai, Israel) placed onto the skin of the left volar forearm. Its temperature was increased from 32 °C by 0.3 °C/s until the subject pressed a button at the first sensation of pain, which triggered cooling of the thermode by approximately 1.2 °C/s. Heat stimuli were applied eight times at random intervals of 25–35 s. The median of the last five responses was defined as the heat pain threshold because in previous experiments a plateau was reached after the first three measurements. Cold stimuli were administered in a similar manner, except that the temperature of the thermode decreased by 1 °C/s from 32 to 0 °C. Five repetitions were used. The cut-off temperatures of the stimulation device were 0 °C and 50 °C. Mechanical stimuli comprised blunt and punctate pressure. The former was exerted perpendicularly onto the dorsal side of mid-phalanx of the right middle finger using a pressure algometer with a circular and flat probe of 1 cm diameter (JTECH Medical, Midvale, USA). The pressure was increased at a rate of approximately 9 N/cm2 per second until the subject reported pain. The procedure was repeated five times every 30 s. Punctate pressure was exerted onto the left volar forearm using von Frey hairs (0.008, 0.02, 0.04, 0.07, 0.16, 0.4, 0.6, 1, 1.4, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 26, 60, 100, 180, 300 g; North Coast Medical Inc., Morgan Hill, CA, USA). Electrical stimuli were applied using a constant current device (Neurometer® CPT, Neurotron Inc., Baltimore, MD). It delivered sine-wave stimuli at 5 Hz applied via two gold electrodes placed on the medial and lateral side of the mid-phalanx of the right middle finger. Their intensity was increased from 0 to 20 mA by 0.2 mA/s until the subjects interrupted the current by releasing a button. Measurements were repeated five times every 30 s. Sensitization was assessed with punctate mechanical and heat11 stimuli and obtained using capsaicin cream (0.1 g, 0.1%, manufactured by the local pharmacy) applied onto a 3 × 3 cm skin area on the left volar forearm and covered with a plaster for 20 min. For cold stimuli12 a menthol solution (2 ml of a 40% menthol solution dissolved in ethanol) was used instead of capsaicin creme.

Data analysis

The goal of the data analysis was to (1) identify structure in the pain threshold data reflecting the prior classification of study participants by sex, (2) to determine which variables among pain threshold drive this structure, and (3) to translate this into a molecular hypothesis for sex-dependent pain perception and treatment. A variety of analytical techniques have been applied, including artificial intelligence (AI) methods selected from its currently most widely used subfield, machine learning. Overviews of the goals and applications of machine learning in pain research have been provided elsewhere10,13. In the present analyses, the focus was on detecting relevant structure in the data consistent with sex segregation. This was addressed using unsupervised and supervised methods. The main difference is the prior class labeling of the cases, i.e., in unsupervised analysis, the data structure is detected without knowledge of the class structure. In supervised methods, the algorithms are given training data, i.e., variables obtained from the cases, to learn the assignment of a case to a particular class. The success of this learning process is supervised because the class labels of the training samples are known. Only later, the trained algorithms have to prove their learned skill on new cases, using the same kind of variables they were trained with to assign a case to a particular class. Perhaps a school analogy will make this clearer: during learning, the “teacher/supervisor” (researcher/programmer) supervises the learning progress of the algorithms based on the knowledge of the correct result. Only when the task has been successfully learned can the algorithm be trusted to assign the correct class label (in this case, male/female) to new cases. These were available as a 20% validation sample, separated from the data before the algorithms were trained (see below). Both classes of analysis benefit from eliminating unnecessary information from relevant content, which is a standard part of machine learning workflow referred to as feature selection14. In the present analysis, several methods from both classes have been applied to obtain robust and internally validated results not relying on a single method.

The programming was performed in the R language15 using the R software package6, version 4.2.2 for Linux, available from the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) at https://CRAN.R-project.org/, and in the Python language16 using Python version 3.8.13 for Linux, available free of charge at https://www.python.org. Analyses were performed on 1–64 cores/threads on an AMD Ryzen Threadripper 3970X (Advanced Micro Devices, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) computer running Ubuntu Linux 22.04.1 LTS (Canonical, London, UK), except that deep learning neural networks were trained on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 graphics processing unit (GPU) (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing consisted of log-transformation and imputation of censored data described in full detail in the supplementary materials. This provided a 125 × 11 sized input data space, X, of pain thresholds (125 subjects, 11 variables; Fig. 2), while the output data space, y, consisted of the binary sex information.

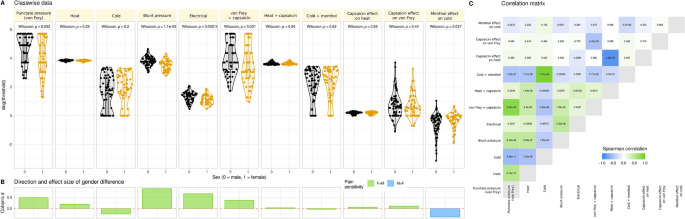

Pain thresholds data and basic statistical assessments. (A) Log10-transformed threshold to mechanical, electrical, or thermal noxious stimuli and the effects of hypersensitization by local application of capsaicin or menthol. Individual data points are presented as dots on violin plots showing the probability density distribution of the variables, overlaid with box plots where the boxes were constructed using the minimum, quartiles, median (solid line inside the box) and maximum of these values. The whiskers add 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) to the 75th percentile or subtract 1.5 times the IQR from the 25th percentile. At the top of the panels are the p values of the statistical comparisons for sex. (B) Direction and size of effect quantified using Cohen’s d. Because for cold stimuli higher threshold values mean higher pain sensitivity whereas for mechanical and heat stimuli, lower threshold values mean higher pain sensitivity, the direction of differences seems inconsistent. Therefore, the columns are colored for the direction of sex differences. (C) Correlation matrix of pain thresholds. Each cell is colored according to the correlation coefficient and labeled with the respective p value. The figure has been created using the R software package (version 4.2.2 for Linux; http://CRAN.R-project.org/6) and the R library “ggplot2” (https://cran.r-project.org/package=ggplot27).

Unsupervised analyses

Unsupervised methods were applied to analyze the univariate modal distribution of variables and cluster structures in the multivariate data space. Unsupervised methods included Gaussian mixture modeling for univariate data, five different and projection methods for multivariate data (principal component analysis (PCA)17, independent component analysis (ICA)18, multidimensional scaling (MDS)19,20, isomap21 and t-distributed stochastic neighborhood embedding (t-SNE)22) and seven different clustering methods (k-means clustering23, partitioning around medoids (PAM)24, hierarchical clustering with Ward’s25, average, single, median and complete linkage). Details and results of the unsupervised analyses are reported in the supplementary materials.

Supervised analyses were performed in which machine learning algorithms were trained to infer the sex of the subjects from pain-related information. Supervised methods included five different machine learning algorithms (support vector machines (SVM)26, random forests27,28, logistic regression29, linear discriminant analysis (LDA)30 and a “deep learning”31 neural network32,33). Set-up and results of supervised analyses are described in detail as follows.

Supervised analyses

Supervised structure detection assumed that if a computational algorithm can be trained with pain threshold data to assign a subject to the correct class, i.e., sex, so that it can infer the sex of new subjects from their pain threshold pattern, then the pain thresholds contain information that is actually relevant to the sex of the subjects.

Supervised analyses were performed using cross-validation and training/test/validation splits of the data set. Specifically, prior to feature selection and classifier training, a class-proportional random sample of 20% of the dataset was set aside as a validation sample that was not touched further during algorithm training and feature selection. The 80/20% split of the data set was done in an automated manner using our R package “opdisDownsampling” (https://cran.r-project.org/package=opdisDownsampling), which selected from 106 random samples the one in which the distributions of the variables were most similar to those of these variables in the complete data set34. The remaining 80% of the dataset were considered as training sample, in which feature selection and classifier training were performed, using further training/test splits of this “training” sample in cross-validation settings; however, without touching the 20%-validation sample.

Feature selection

Feature selection aimed at filtering the “needles” from the “haystack”, i.e., identifying the relevant pain threshold variables for the sex differences. Several feature selection methods were used14 available in the Python package “scikit-learn” (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/35). Univariate methods were used that are based on the false positive rate test and the family wise error rate. Multivariate feature selection methods were used that are based on calculation of an importance estimate for each variable following training of four different classification algorithms (SVM, random forests, logistic regression, LDA). After training of the algorithms, the most relevant variables were selected using methods from the “sklearn.feature_selection” module of scikit-learn. This included the F value based feature selection as implemented in the “SelectKBest” method. The number k of the features to be selected was determined by a grid search of [1,…,11] variables. Further methods comprised “SelectFromModel” (SFM), which selects features based on importance weights in the trained algorithm, recursive feature elimination (RFE), which selects features, by recursively considering smaller and smaller feature sets and generating a feature ranking, forward and backward sequential feature selection (SFS), which iteratively find the best features by adding features to a set of initially zero and all features, respectively. Furthermore, the generic permutation importance provided in the “permutation_importance” method of the “sklearn.inspection” package was used, setting the number of permutations to n_repeats = 50. The feature selection methods were applied in a 5 × 20 nested cross-validation scenario provided with the “RepeatedStratifiedKFold” method from the “sklearn.model_selection” module of “scikit-learn”, setting the parameters “n_splits” = 5 and “n_repeats” = 20. All classifiers used during feature selection were tuned with respect to relevant hyperparameters.

With the two univariate methods and the six multivariate methods run with four classification algorithms, the total number of feature selection methods summed to m = 26. In the resulting 11 × 26 feature matrix, i.e., 11 pain threshold variables versus 26 selection methods, initially filled with zeros, each feature received a value of 1 when selected. This resulted in a sum score for the number of selections for each pain-related variable. The final feature set was obtained from the majority vote of the 26 selection methods. Therefore, the sum score was submitted to computed ABC (cABC) analysis36, an item categorization technique that divides a set of positive numerical data into three disjoint subsets labeled “A” to “C”. Subset “A” contains the “important few”, which were retained as “reduced” feature sets, whereas subset C” contains the “trivial many”37. The Python implementation is available as our package “cABCanalysis” at https://pypi.org/project/cABCanalysis/38.

Classifier performance evaluation

The main classifiers were imported from the Python package “scikit-learn” (https://scikit-learn.org/stable/35). SVM, implemented as “linearSVC” and random forests were selected as two commonly used classification algorithms of different types, i.e., class separation using hyperplanes in data projected to higher dimensions, or class separation using an ensemble of simple decision trees. In addition, logistic regression and LDA were included as classical methods for class assignment. For comparison, a “deep learning”31 neural network32,33 was used to include a completely different type of classifier, using the GPU-only version of the “TensorFlow” machine learning platform (https://www.tensorflow.org39) for Python.

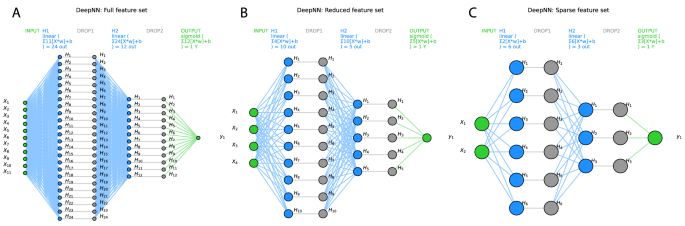

The classifiers were tuned to the respective training data set using a grid search approach for different combinations of hyperparameters. For example, the tuning of the algorithms led to the selection of ridge regression as the regularization method for SVM and logistic regression, to a forest size of d = 500 trees with a maximum depth of 1 decision for random forests. For the deep neural network, after grid searches including the number of layers, number of neurons, several activation functions provided in “TensorFlow”, the number of hidden layers was set to h = 2, the number of neurons in layer 1 was set to int((nfeatures + 1)/0.5) and the number of neurons in layer 2 was set to int((nfeatures + 1)/1). A dropout layer with a rate of 0.2 was added after each layer to reduce possible overfitting. The activation functions were linear between the hidden layers and sigmoidal for the binary (men = 0, women = 1) output layer (Fig. 3). Binary crossentropy was set as the loss function, and 1000 epochs were used to train the neural network.

Visualization of the deep neural network architecture of the TensorFlow model used in the present analysis with (A) the full feature set (d = 11 pain-threshold related variables), d = 4 variables that had resulted from the feature selection steps shown in Fig. 4 as “reduced” feature set (B) (darker blue columns Fig. 4A), or d = 2 variables that had resulted from further narrowing the feature set to the “sparse” feature set (C) (darkest blue columns Fig. 4A). Variables X1..11 are the input variables, H1..n denotes the hidden layers, and the binary output layer is shown on the right. In addition, the respective activation functions are given on the top of each layer. The graph shows the neural networks architectures as implemented with “TensorFlow” and run on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The figure was created using Python version 3.8.13 for Linux (https://www.python.org), with the seaborn statistical data visualization package (https://seaborn.pydata.org40) and Python code modified from https://towardsdatascience.com/deep-learning-with-python-neural-networks-complete-tutorial-6b53c0b06af0.

After feature selection, it was tested whether the selected pain threshold variables actually provided sufficient information for sex separation in a sample that was not available during classifier tuning and feature selection. Therefore, the included algorithms were trained with the full and reduced feature sets in a 5 × 20 nested cross-validation scenario, using randomly selected subsets of 67% of the original training dataset. The trained classifiers were then applied to random subsets comprising each 80% of the validation dataset that had been separated from the full original dataset prior to feature selection and classifier tuning. For the reduced feature sets, hyperparameter tuning was repeated prior to classifier performance evaluation. Balanced accuracy was used as the main parameter to evaluate the classification performance41. Additionally, the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (roc-auc)42 was calculated. To control possible overfitting, all machine-learning algorithms were trained with pain data in that each variable was randomly permuted, with the expectation that a classifier trained with this information should not perform better than guessing, i.e., give a balanced accuracy (or a roc-auc) around 50%, else, overfitting could not be ruled out entirely. Furthermore, using a validated approach to the most informative features43, classifiers were also trained with the unselected features, i.e., the pain threshold variables that were kept as the result of feature selection. This provided further support that the feature selection had indeed identified the key informative variables.

Hypothesis transfer to the level of molecular pharmacology

From the machine-learning based analysis of the sex-related information contained in pain thresholds, a molecular hypothesis for sex-dependent pain perception and treatment could be derived that narrowed the molecular background on nociceptors for mechanically but not thermally induced pain. This was addressed via knowledge retrieval from publicly accessible databases. Relevant nociceptors were identified by domain expert knowledge and classical literature search among biomedical publications in the PubMed database. The evidence on the molecular background of pain induced by mechanical stimuli provided a basis for potential translation into precision pain medicine approaches.

To transfer this in a pharmacological context, information about drugs and their molecular targets was queried from the DrugBank database44 at https://go.drugbank.com (version 5.1.9 dated 2022-01-04). The database was downloaded as an extensible markup language (XML) file from https://go.drugbank.com/releases/5-1-9/downloads/all-full-database. The information contained in it was processed using the R package “dbparser” (https://cran.r-project.org/package=dbparser45). The drug targets were available encoded as Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) (https://www.uniprot.org46) IDs and converted into NCBI numbers of the coding genes using the R library “org.Hs.eg.db” (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/org.Hs.eg.db.html47). Approved or investigational drugs with human targets were retained.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study from which the data set originates followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical Faculty of the Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany (approval number 150/11).

Informed consent

Permission for anonymized reports of data analysis results obtained from the acquired information was included in the informed written consent.