Overview of the proposed method

In this study, we propose a framework that leverages multiview images of ancient glass beads captured from top and side perspectives to complement three-dimensional shape characteristics and view-dependent features that are difficult to capture from a single viewpoint. To extract image features, we integrate CNNs, which excel at capturing local textures and shape patterns, with ViTs, which are effective at extracting global contextual features and long-range dependencies.

However, previous hybrid architectures such as Conv-ViT15, which combine convolutional and transformer-based modules suffer from several practical limitations. Their three-branch parallel design introduces high computational costs, and their simplistic late-fusion strategy fails to align cross-model features effectively. In contrast, our framework adopts a lightweight two-branch structure and introduces bidirectional knowledge distillation to explicitly align and integrate representations between CNNs and ViTs while maintaining computational efficiency.

The central idea of our approach lies in the application of bidirectional knowledge distillation between different model architectures (CNN and ViT) and between different viewpoints (top and side images). Knowledge distillation is a technique in which one model (the student) learns from another model (the teacher) by imitating its output distributions or internal representations, effectively transferring the teacher’s learned knowledge16,17,18. In our bidirectional setting, this process is extended into a mutual exchange of knowledge, where both models act as teacher and student simultaneously, refining each other’s outputs though iterative learning. In the context of ancient artifact classification, where the number of available samples is inherently limited, such a mechanism is particularly valuable. By facilitating mutual knowledge transfer between models and viewpoints, the proposed method allows the network to extract and integrate richer information even from scarce training data. This strategy enables more effective fusion of complementary feature representations from each modality, improving consistency across models and viewpoints and ultimately enhancing classification performance.

Multi-view integrated distillation network

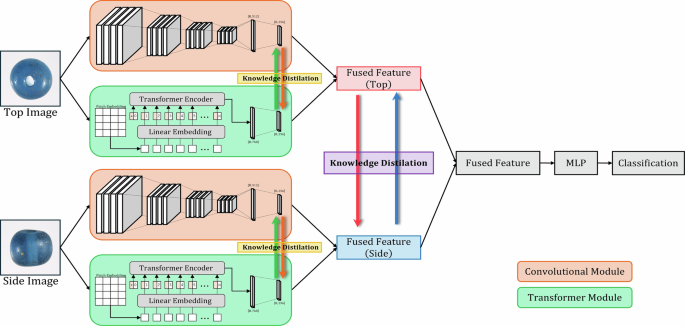

To this end, we propose MidNet (Multiview Integrated Distillation Network) shown in Fig. 2, which combines the complementary feature extraction capabilities of CNNs and ViTs with multiview image data to improve classification accuracy for ancient glass bead images. The proposed method performs mutual knowledge distillation across both models and views to facilitate effective feature integration.

Schematic illustration of the proposed bi-directional knowledge distillation framework operating across models and viewpoints.

Generally, CNNs are well-suited for capturing fine-grained local structures such as detailed shapes and textures. In contrast, ViTs, through the use of self-attention mechanisms, are capable of modeling global contextual information and long-range dependencies. These two architectures possess fundamentally different inductive biases, and their integration is expected to yield more comprehensive feature representations. In the context of ancient glass bead classification, both local surface patterns (e.g., texture irregularities or color variations) and global morphological characteristics (e.g., overall shape and contour) play essential roles in distinguishing between different bead types. Therefore, fusing CNN and ViT architectures enables the model to effectively learn both detailed and contextual visual information, leading to improved discriminative capability for this specific archaeological classification task.

Based on this perspective, we introduce a bidirectional knowledge distillation framework in which the CNN and ViT branches are trained in parallel while exchanging soft-target information. For each branch, the distillation loss is computed as the symmetric Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the output distributions of the two models. Specifically let Lce be the standard cross-entropy loss of each model and Lkd be the bidirectional KL divergence defined as

$${L}_{kd\_model}=\frac{1}{2}\left[KL\{\log {\rm{softmax}}({\rm{CNN}}),\,{\rm{softmax}}({\rm{ViT}})\}\,+\,KL\{\log {\rm{softmax}}({\rm{ViT}}),\,{\rm{softmax}}({\rm{CNN}})\}\right]$$

(1)

In our framework Lkd_model is added to the standard cross-entropy loss used in the ensemble training of the CNN and ViT yielding the following total loss for optimization:

$$L={L}_{ce}+\lambda {L}_{kd\_model}$$

(2)

This formulation effectively introduces a penalty term based on the discrepancy between the output distributions of the CNN and ViT, encouraging the two branches to produce consistent predictions while leveragingtheir complementary representations.

By incorporating Lkd_model with an appropriate weight λ, we aim to achieve a more effective and stable learning process compared with using cross-entropy loss alone. As a result, the combined framework yields richer feature representations that cannot be obtained by either model individually.

The glass bead images used in this study were captured from two distinct viewpoints (top and side), each containing complementary, view-dependent information such as shapes and patterns. Utilizing multiple viewpoints enables the model to capture features that cannot be fully observed from a single perspective, such as three-dimensional aspects of morphology, surface texture, and color variations, thereby supporting a more human-like recognition ability. We limited imaging to these two directions because ancient glass beads typically exhibit a high degree of symmetry, often approximating a toroidal (doughnut-like) structure. Thus, top and side views provide essential complementary information for classification without introducing redundant perspectives. In addition, restricting the dataset to two views offers a balanced trade-off between richness of information and efficiency of computation.

Owing to the structural and visual correlations between these viewpoints, we extend the mutual knowledge distillation framework to operate across viewpoints as well as across model architectures. Specifically, bidirectional distillation is applied between the top and side branches, with the distillation losses defined as

$${L}_{kd\_view}=\frac{1}{2}\left[KL\{\log {\rm{softmax}}({\rm{Top}}),\,{\rm{softmax}}({\rm{Side}})\}+KL\{\log {\rm{softmax}}({\rm{Side}}),\,{\rm{softmax}}({\rm{Top}})\}\right]$$

(3)

Thus, the total loss for training each model is computed as

$$L={L}_{ce}+\lambda ({L}_{kd\_model}+{L}_{kd\_view})$$

(4)

where λ is a weight coefficient controlled the relative contribution of the combined distillation terms. In this framework, knowledge distillation is first performed between architectures (CNN ↔ ViT) and then across viewpoints (Top ↔ Side), allowing the model to integrate both architectural and viewpoint-specific information. This two-stage distillation scheme encourages unified and consistent feature representations, effectively leveraging multimodal visual information and enhancing the robustness of classification across both models and perspectives.

Dataset and preprocessing

We constructed our dataset using 3434 images of ancient glass beads, each of which has been classified based on detailed observation and analysis. The beads were excavated from archaeological sites across Japan, spanning the Yayoi to Kofun periods. All images were captured in a controlled laboratory environment, with temperatures maintained between 22 °C and 27 °C and relative humidity between 40% and 60%, to minimize light and environmental interference. Each data sample includes a pair of images captured from two distinct viewpoints: Top and Side. The top view refers to an image taken from the direction where the central hole of a ring-shaped bead is visible and where distinctive features are typically recognized by experts, while the side view refers to an image taken from an arbitrary lateral direction when the bead is placed with the top facing upward.

The images were acquired using two different imaging systems depending on the period of documentation: (1) a stereomicroscope (Leica M205C) combined with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-Ri1 camera (since April 2017), and (2) a stereomicroscope (Leica MZ16) combined with a Nikon DXM1200F camera (from 2008 to March 2016). Thus, the imaging devices varied based on the time of acquisition. However, no color correction or other preprocessing was applied without additional annotations, such as expert labeling or supplementary labeling. The classification task comprises 16 classes, and the number of samples per class is summarized in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, the dataset exhibits substantial class imbalance. In addition, some beads show physical damage due to aging or excavation conditions. To address these issues, we mainly applied two preprocessing strategies.

First, to mitigate the impact of class imbalance, we employed image generation using Stable Diffusion19,20. Specifically, for classes with fewer than 20 original samples (LI, LIIB, SIIIA, SVB, SVC, mix-Al), synthetic images were generated. In the revised setting, for each image belonging to a minority class within the training split of the k-fold cross-validation, we generated one synthetic image. Importantly, these generated images were applied only to those samples assigned to the training split within the k-fold cross-validation scheme, and no synthetic images were included in any validation fold. These generated samples were used exclusively for training. We chose to use synthetic images because the number of available artifacts directly reflects the actual number of excavated items. For classes with fewer excavated samples, it is inherently difficult to increase the dataset size with real-world images, making image generation a practical alternative. The Diffusion model used was the pre-trained Stable Diffusion v1.5 model, and no fine-tuning was performed specifically for the ancient glass beads.

Although Stable Diffusion has demonstrated effectiveness in general image generation, its quality for and applicability to specialized domains such as archaeological artifacts have not been previously validated. In this study, the effectiveness of using generated images was confirmed through preliminary experiments comparing classification performance with and without synthetic images. Across all baseline models, including ResNet18 and ViT, the inclusion of synthetic images led to improvements in classification performance, with an average increase of 0.11% in accuracy and 0.20% in macro F1 score. While these gains may appear modest, they are significant given the strong class imbalance in the dataset. Notably, the augmentation particularly enhanced the recognition of underrepresented classes, justifying the inclusion of generated images in our training pipeline.

In addition, although only a small portion of the beads exhibited physical damage (e.g., chipping or abrasion), we aimed to improve the model’s robustness against such irregularities by applying several data augmentation techniques during training. Specifically, we employed RandomResizeCrop, a common augmentation technique that randomly crops and resizes an image to simulate variations in object scale and viewpoint, to introduce scale variation while maintaining the essential structure of the bead. We also used ColorJitter, which perturbs image brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue, to simulate natural differences in lighting and color conditions across excavation environments.

To further enhance robustness against localized defects, we applied RandomErasing, an augmentation method that randomly masks rectangular regions within the input image, with a probability of 0.1. In our implementation, the erased regions covered 0.5–5% of the image area and had aspect ratios between 0.3 and 3.3. This operation reduces overreliance on damaged or visually noisy areas and promotes more generalizable feature learning.

For validation, only normalization was applied to ensure fair comparison without additional stochastic perturbation. All images were kept at 224 × 224 pixels and normalized using a mean of 0.5 and standard deviation of 0.5 for each RGB channel, matching the values for the training pipeline.

These preprocessing procedures were carefully designed to enhance model robustness to physical defects, improve invariance to appearance variations, and ensure consistent input normalization across experiments.

Training setting

All experiments were conducted on an Amazon Web Services g4dn.x4large instance equipped with an NVIDIA T4 GPU (16GB VRAM), an Intel Xeon processor, and 64GB of system memory. The software environment was based on Ubuntu 24.04, with development implemented in Python 3.12.10, PyTorch 2.8.0, and torchvision 0.23.0.

To evaluate the performance of the models, we employed 5-fold cross-validation. We used the StratifiedKFold method to preserve the class distribution within each fold. This approach is particularly effective for our imbalanced dataset, ensuring fair evaluation across both training and validation sets.

All models were implemented using the PyTorch framework. Training was performed for 10 epochs with a batch size of 32. The optimizer used was AdamW with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4 and a weight decay coefficient of 1 × 10−2. To standardize optimization, we employed a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler (CosineAnnealingLR), which gradually decreased the learning rate from its initial value to a minimum of 1 × 10−5 over the course of training. For the loss function, we used cross-entropy with both class weighting and label smoothing. The class weights were computed based on the class distribution using

$${w}_{i}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\log (1+sample{s}_{i})}}$$

(5)

and normalized across all classes. This weighting compensates for class imbalances by assigning larger weights to minority classes. Additionally, label smoothing (ϵ = 0.1) applied to improve generalization and reduce overconfidence in the prediction.

The distillation coefficient λ was set to 0.2. This value was determined empirically by conducting preliminary experiments using the Top-view images of the ancient glass beads, in which the dataset was divided according to a Train:Test ratio of 8:2 and λ was varied from 0.0 to 0.5 in increments of 0.1. Based on this analysis, λ = 0.1 resulted in the highest performance in terms of both accuracy and macro F1 score as shown in Table 3, and this value was therefore adopted in all subsequent experiments.

Compared Methods

We compared the following representative baseline models:

-

ResNet18: a standard CNN architecture21.

-

ViT: a Transformer-based visual model

-

HCTNet (Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network): a model that simply fuses features from both CNN and ViT

-

MidNet: a hybrid model that integrates bidirectional knowledge distillation across multiple models and viewpoints

Both ResNet18 and ViT were initialized with pretrained weights from ImageNet-1k. ImageNet-1k is a large-scale benchmark dataset consisting of approximately 1.2 million training images and 50,000 validation images across 1000 object categories, and it has been widely used for pretrained deep learning models in computer vision. During training, all pretrained parameters were kept unfrozen, and the entire network was fine-tuned end-to-end for the classification task, rather than updating only the final fully connected layers.

HCTNet is inspired by the previously proposed Conv-ViT framework and integrates convolutional layers with self-attention mechanisms. While HCTNet shares conceptual roots with Conv-ViT, it incorporates unique modifications to its architecture and training procedure. In this study, it is treated as an independent baseline.

MidNet, the proposed method, is designed as an enhanced hybrid model that performs mutual knowledge distillation between both models and viewpoints. This enables more effective integration of complementary feature representations.

Through these comparisons, we aim to clarify the relative performance of different model architectures and input strategies in the classification of ancient artifacts from multiview images.

Evaluation metrics

To quantitatively assess classification performance, we used accuracy, macro F1 score, Cohen’s κ coefficient and confusion matrices as primary evaluation metrics. The macro F1 score was calculated by computing the F1 score independently for each class and then taking the unweighted average, ensuring that all classes contributed equally regardless of class imbalances. Cohen’s κ coefficient was included to account for chance agreement, providing a more robust evaluation in settings with uneven class distributions. Confusion matrices were also analyzed to capture classwise prediction behavior and to identify specific misclassification patterns. In this study, the confusion matrix was constructed by aggregating the predictions from all test splits in the 5-fold cross-validation, thereby providing a comprehensive visualization that approximates the model’s performance on the entire dataset.

Furthermore, we evaluated the computational efficiency of each model by reporting its number of floating-point operations (FLOPs). As shown in Table 4, this comparison highlights the computational cost of each architecture and helps clarify the trade-off between model complexity and classification performance, which is particularly relevant for potential deployment in resource-limited archaeological settings.